Let's talk about a number that can tell you more about your business health than almost any other single metric. It's not your revenue. It's not your net profit. It's your inventory turnover.

I've consulted for dozens of businesses over the years, from small boutique retailers to mid-sized manufacturers. The ones struggling with cash flow, drowning in storage fees, or constantly running sales to clear out old stock? They almost always have one thing in common: they don't understand or actively manage their inventory turnover ratio. They're flying blind.

This isn't just accounting theory. This is the pulse of your operational efficiency.

What's Inside?

- What Inventory Turnover Really Measures (And What It Doesn't)

- How to Calculate Inventory Turnover: The Formula Demystified

- Interpreting Your Ratio: What's a "Good" Number?

- The 3 Most Common (and Costly) Calculation Mistakes

- Actionable Strategies to Improve Your Inventory Turnover

- Beyond the Basics: Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO)

- Your Burning Questions Answered

What Inventory Turnover Really Measures (And What It Doesn't)

At its core, the inventory turnover formula tells you how many times a company has sold and replaced its inventory during a specific period, usually a year. Think of it as the velocity of your stock.

Are your products flying off the shelves and being restocked six times a year? That's high velocity. Are they gathering dust, turning over just once? That's a major red flag.

But here's the nuance most articles miss: a high ratio isn't inherently good, and a low ratio isn't inherently bad. It's all about context. A luxury yacht dealer will have a fantastically low turnover—maybe 0.5 times a year. That's their business model. A grocery store selling milk and bread needs a high turnover—dozens of times a year.

The real power of this metric is in the trend. Is your turnover increasing year over year? That generally indicates improving efficiency. Is it falling? You need to dig into why, and fast.

How to Calculate Inventory Turnover: The Formula Demystified

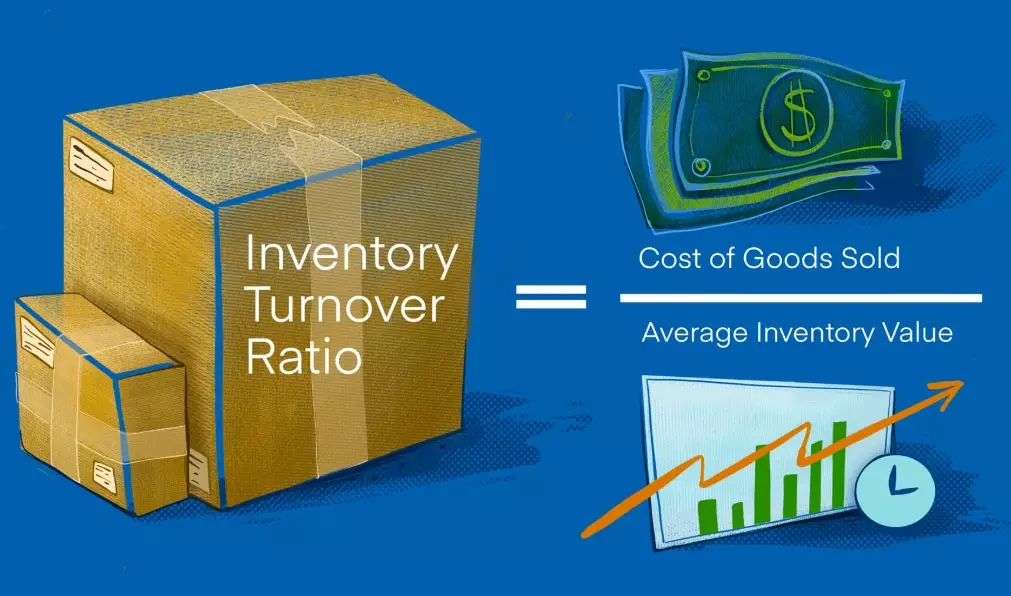

The classic inventory turnover formula is simple:

Inventory Turnover Ratio = Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) / Average Inventory

Let's break down each component, because this is where people trip up.

1. Cost of Goods Sold (COGS)

This is the direct cost of producing the goods you sold in a period. For a retailer, it's the wholesale price you paid. For a manufacturer, it's raw materials, labor, and overhead directly tied to production. Do not use sales revenue here. Using revenue will inflate your ratio and give you a completely false sense of security. This is mistake #1 for many new business owners.

You can find your COGS on your income statement.

2. Average Inventory

You can't just use the inventory value from December 31st if you're calculating an annual ratio. Why? Maybe you stocked up for the holidays. That end-of-year snapshot is distorted.

You need an average. The most practical way is to take your beginning inventory value for the period and your ending inventory value, add them together, and divide by 2.

Average Inventory = (Beginning Inventory + Ending Inventory) / 2

For a more accurate picture, some businesses use quarterly or even monthly averages. For most, the simple two-point average works just fine to spot trends.

A Real-World Walkthrough: Brew & Bean Coffee Roasters

Let's say my small-batch coffee company, Brew & Bean, had the following numbers last year:

- COGS (cost of green coffee beans, packaging, roasting labor): $120,000

- Inventory value on January 1: $15,000

- Inventory value on December 31: $25,000

First, find the average inventory: ($15,000 + $25,000) / 2 = $20,000.

Now, plug it into the formula: $120,000 / $20,000 = 6.

Brew & Bean's inventory turned over 6 times last year. On average, we held a stock of coffee beans that cost us $20,000, and we sold through that equivalent amount six times.

Interpreting Your Ratio: What's a "Good" Number?

This is the million-dollar question. The answer is profoundly unsatisfying: It depends.

Your ideal ratio is dictated by your industry, product type, and business model. Selling fresh flowers is different from selling diamond rings.

| Industry / Business Type | Typical Turnover Ratio Range (Annual) | Why It Varies |

|---|---|---|

| Grocery Stores | 14 - 20 | Perishable goods, high volume, low margins. |

| Auto Dealerships | 2 - 4 | High-value items, longer sales cycles. |

| Apparel Retail | 4 - 6 | Seasonality, fashion trends. |

| Restaurants | 20 - 30+ | Extremely perishable inventory (food). |

| Manufacturing (Machinery) | 1 - 3 | Complex, custom-built items. |

Your first stop for a benchmark should be industry reports. Associations like the National Retail Federation (NRF) or your specific trade group often publish financial ratio studies.

But more important than any industry average is your own historical trend. Plot your ratio quarterly. Is the line going up or down? A downward trend demands investigation—are you over-ordering? Are certain products becoming obsolete?

The 3 Most Common (and Costly) Calculation Mistakes

After reviewing countless financials, I see the same errors repeatedly.

Mistake 1: Using Sales Instead of COGS

We touched on this. It makes your efficiency look amazing but is completely wrong. If Brew & Bean had $300,000 in sales and used that number, our ratio would be 15 instead of 6. We'd think we were world-class, missing the real picture.

Mistake 2: Using a Single Inventory Snapshot

Using only the year-end inventory value is like judging a movie by its last frame. It ignores the entire story of the year. Always use an average.

Mistake 3: Ignoring Inventory Composition

This is the advanced mistake. Your overall ratio might be a healthy 5. But what if 80% of your turnover comes from 20% of your products (the fast-moving ones), while the other 80% of your stock barely moves? Your overall number hides a graveyard of slow-moving inventory tying up your cash.

The fix? Calculate turnover by product category or even by SKU for your key items. This granular view is where the real insights for improvement live.

Actionable Strategies to Improve Your Inventory Turnover

So your ratio is lower than you'd like. Now what? Here are concrete steps, not platitudes.

1. Master Demand Forecasting. Stop guessing. Use your historical sales data, factor in seasonality and marketing plans, and create a simple forecast. Tools don't have to be fancy—a well-built spreadsheet is better than intuition. The goal is to buy what you need, when you need it.

2. Implement a "Fast/Slow Movers" Analysis. Every quarter, categorize your products:

- A Items: High sales velocity (fast movers).

- B Items: Moderate sales.

- C Items: Slow movers.

Your strategy? Ensure A items are never out of stock. Scrutinize every reorder of B items. For C items, stop automatic reordering. Consider a final clearance sale to liquidate them and free up capital and space.

3. Negotiate Better Terms with Suppliers. Can you move to smaller, more frequent deliveries? This reduces the average inventory you hold. Even better, can you adopt a vendor-managed inventory (VMI) system for key items? The supplier monitors your stock and replenishes it, shifting some holding cost and risk to them.

4. Review Your Purchasing Process. Is one person buying based on a "good deal" rather than actual demand? Centralize and data-fy purchasing. A 50% discount on a truckload of something you'll sell in three years is not a good deal.

Beyond the Basics: Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO)

Once you're comfortable with the turnover ratio, take the next step: calculate Days Inventory Outstanding (DIO). This translates your ratio into a more intuitive concept—the average number of days you hold inventory before selling it.

DIO = (Average Inventory / COGS) x Number of Days in Period

Using Brew & Bean's annual numbers: ($20,000 / $120,000) x 365 days = 60.8 days.

On average, a bag of coffee beans sits in our warehouse for about two months before it's sold. This is a powerful communication tool. Telling your team "we need to reduce our DIO from 60 days to 50 days" is clearer than "we need to improve our ratio from 6 to 7.3."

Your Burning Questions Answered

How often should I calculate my inventory turnover?

For most businesses, calculating inventory turnover quarterly is the sweet spot. This frequency is frequent enough to catch seasonal trends or sudden supply chain hiccups without creating analysis paralysis. Monthly calculations can be useful for fast-moving industries like perishable goods or fast fashion, but for the average retailer or manufacturer, quarterly provides a stable, actionable view. Annual calculations are practically useless for management—they're just a historical footnote.

My inventory turnover ratio is high. Is that always good?

Not necessarily. A very high ratio can be a red flag for stockouts. It might mean you're selling out so fast that you're constantly missing sales opportunities because you don't have product on the shelves. I've seen businesses brag about a high turnover, only to find their customer satisfaction scores were plummeting due to frequent unavailability. The goal isn't an infinitely high number; it's the optimal number that balances sales velocity with having enough stock to meet demand.

What's the most common mistake businesses make with the inventory turnover formula?

Hands down, it's using the wrong Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) figure. Many small businesses mistakenly use total sales revenue in the numerator, which inflates the ratio and gives a completely false sense of efficiency. Others use a COGS figure that doesn't match the inventory period. If your inventory value is an average for Q2, your COGS must also be for Q2. Mismatching these time periods renders the calculation meaningless. Always double-check that your COGS aligns perfectly with the period for which you averaged your inventory.

Can I compare my inventory turnover ratio directly with a competitor's?

You must be extremely cautious. Direct comparison is often misleading unless you're in the identical niche with a similar business model. A high-end furniture store and a discount electronics retailer will have wildly different 'good' ratios. A better approach is to use industry benchmarks from sources like the National Retail Federation or industry-specific associations as a broad guide, but focus primarily on tracking your own ratio's trend over time. Improving your own number is more important than beating an arbitrary industry average.

Start with one calculation. Use last year's numbers. See what you get. That number, whether it's 2 or 20, is the starting point for a more efficient, more profitable business. It turns guesswork into a managed process. And that's the real goal.