Let's be honest. Most people think of a feasibility study as a bureaucratic hurdle. A box to check before the real work begins. A formality to please the board or secure funding. I've sat through presentations where the "study" was a 20-page document that essentially said, "This is a great idea, let's do it." And then, twelve months and several hundred thousand dollars later, the project is quietly shelved.

That's not a feasibility study. That's a fairy tale.

A real feasibility study is a merciless interrogation of your idea. Its primary job isn't to find a way to say yes. Its job is to find every possible reason to say no. It's the cheapest and most valuable insurance policy you can buy for any project, business venture, or major investment. Skipping a rigorous one, or doing a superficial one, is like buying a house because you liked the paint color without checking the foundation.

What's in this guide?

What a Feasibility Study Actually Is (And Isn't)

Think of it as a pre-mortem. Before you invest serious time and capital, you gather your team and ask: "If this project fails in two years, what will have caused it?" You then go out and investigate those potential causes.

It's not a business plan. A business plan is a roadmap for execution, written with the assumption the venture is viable. The feasibility study comes before that. It's the process of determining if you should even draw the map.

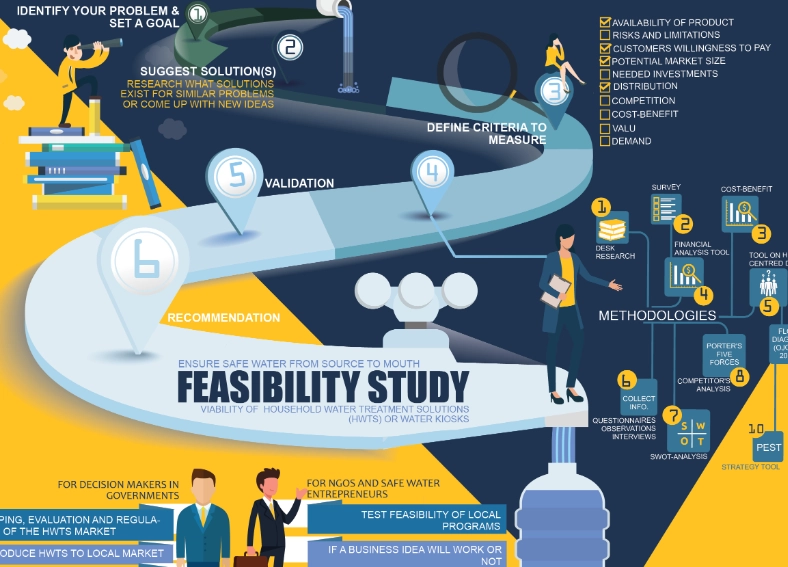

It examines five core areas:

Market & Technical: Is there a real demand, and can we actually build the thing?

Financial & Operational: Can we afford to build and run it, and do we have the capability?

Legal & Scheduling: Are we allowed to do it, and can we do it in a reasonable time?

The output is a feasibility report. This document shouldn't just present data; it should tell a story with a clear recommendation: Go, No-Go, or Go-If (e.g., "Go if we can secure a partner to handle distribution").

How to Conduct a Feasibility Study in 5 Phases

Don't make this more complicated than it needs to be. A structured approach saves time and ensures you don't miss critical blind spots.

Phase 1: Project Scoping & Preliminary Analysis

This is where you define what "feasible" means. You're not researching yet. You're setting the rules of the game. What are the key objectives? (e.g., "Achieve 15% market share in year two" or "Reduce internal processing time by 40%"). What are the non-negotiable constraints? Budget limits, timeline must-haves, regulatory boundaries. Draft a one-page project description. If you can't crisply define the problem and the desired outcome here, everything that follows will be fuzzy.

Phase 2: The Deep-Dive Market Analysis

This is where many studies go off the rails with optimism bias. You must answer: Is there a profitable market?

Don't just look at total market size. That's vanity. Look at serviceable available market (SAM) – the segment you can realistically reach. Then, get even more specific with serviceable obtainable market (SOM) – your realistic share in the first few years. Talk to potential customers. Not just friends, but people who would actually pay. Run surveys. Analyze competitors not just to list them, but to understand their weaknesses and where you can genuinely differentiate. A common mistake? Assuming that because a market is big, there's room for you. A crowded, mature market might be harder to crack than a small, growing niche.

Phase 3: Technical & Operational Assessment

"Can we build it?" seems straightforward, but the devil is in the details. This isn't just about having the technology. It's about:

- Technology Choice: Are we using proven, stable tech or betting on something new and shiny?

- Team Skills: Do we have the talent in-house, or must we hire/outsource? What's the lead time and cost for that?

- Operational Fit: How will this new product/service fit into our current operations? Will it strain our customer service? Overload our logistics?

- Supply Chain & Resources: Can we reliably get the materials? I once advised a food startup whose brilliant recipe depended on a rare, seasonal herb. Their feasibility study missed that sourcing it at scale was impossible. They had to pivot entirely.

Phase 4: Financial Modeling & Funding

Time to crunch numbers. Build a financial model that includes:

Start-up Costs: Everything needed to launch.

Operational Expenses: The cost to run the business month-to-month.

Revenue Projections: Based on your conservative SOM analysis, not pie-in-the-sky dreams.

Break-even Analysis: When do you stop bleeding money?

Funding Requirements: How much cash do you need, and where will it come from? Bootstrapping, loans, investors?

The most important part here is the sensitivity analysis. What if your sales are 20% lower than projected? What if your main material cost increases by 15%? How does that affect your break-even point? If a small change sinks the model, that's a massive risk flag.

A note from experience: People hate building the "worst-case" model. They think it's pessimistic. I think it's prudent. I've never seen a project fail because the feasibility study was too conservative. I've seen dozens fail because it was too optimistic.

Phase 5: Legal, Regulatory, and Risk Synthesis

This is the checklist phase. What permits, licenses, or certifications are required? Are there zoning laws, environmental regulations, or data privacy laws (like GDPR) that impact us? What are the absolute show-stopper risks? Finally, you synthesize all the findings from Phases 2-4. You weigh the market opportunity against the technical challenges and financial hurdles. You don't just list pros and cons; you assess the overall balance and the credibility of your path to success.

A Real-World Example: From "Great Idea" to Harsh Reality

Let's make this concrete. Imagine a talented chef, Maria, wants to open a high-end, authentic Neapolitan pizza restaurant in a mid-sized city.

The Idea: "Artisan pizza using imported ingredients, wood-fired oven, fine dining atmosphere."

The Superficial Study (The Fairy Tale): "People love pizza! The foodie scene is growing here. I'm a great chef. Let's do it!"

The Rigorous Feasibility Study (The Interrogation):

- Market: Research shows the city supports 3 high-end restaurants, all struggling. The "foodie" crowd is small and fickle. The local palate prefers casual, large-portion dining. Competitor analysis reveals a popular gourmet burger place just closed due to high prices.

- Technical/Operational: Finding a location zoned for a wood-fired oven is difficult and expensive. The only qualified oven installer is 300 miles away. Authentic ingredients have a 4-week lead time, complicating inventory.

- Financial: Start-up costs for the oven, renovation, and premium location are 40% higher than initial guesses. To break even, Maria needs to charge $30 per pizza in a market where $18 is considered expensive. Sensitivity analysis shows that a 10% drop in customer traffic makes the business unviable.

- Legal: Health department has strict, costly ventilation requirements for wood-fired ovens.

The Recommendation: No-Go on the original concept. However, the study identified a potential Go-If: A successful local brewery with a large, casual space is seeking a food partner. A scaled-down, pizza-focused counter inside the brewery could work, leveraging their traffic, lower rent, and more casual atmosphere. The study didn't just kill a bad idea; it pivoted to a potentially viable one.

The 5 Most Common (and Costly) Feasibility Study Mistakes

| Mistake | Why It Happens | The Real-World Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmation Bias | The team is already in love with the idea. They seek data that supports it and ignore red flags. | The study becomes a sales document, not an analysis. It greenlights doomed projects. |

| Underestimating Operational Feasibility | Focus is on the "what," not the "how." The day-to-day grind of running the new operation isn't fully thought through. | The product launches, but the company can't support it. Customer service collapses, quality fails, costs balloon. |

| Using Best-Case Scenarios as Averages | Optimism feels better. The financial model assumes everything goes perfectly. | The project runs out of money halfway through. It either fails or requires emergency funding at terrible terms. |

| Relying Solely on Desk Research | It's easy to find market reports and competitor websites. Talking to real customers is hard. | You build a solution for a problem that doesn't exist, or that people won't pay to solve. |

| No Clear Go/No-Go Criteria | The study ends with a pile of data but no framework for decision-making. | Leadership makes an emotional, political, or rushed decision, negating the study's value. |

The Final Step: Making the Go/No-Go Decision

The report is done. Now what? The decision should not be a democracy where everyone votes. It should be a structured evaluation against the criteria you set in Phase 1.

Present the findings honestly. The recommendation should be clear. If it's a "Go," the report is your foundation for the detailed business plan. If it's a "No-Go," celebrate. You just saved an enormous amount of money, time, and heartache. Document the lessons learned and move the team's energy to a more promising idea.

If it's a "Go-If," the conditions must be specific and actionable. "Go if we can secure a distribution partner within 90 days." Then, your next step is not full launch; it's a focused effort to meet that condition.

Your Burning Questions Answered

When is the best time to conduct a feasibility study for a new business idea?

Conduct it immediately after the initial concept solidifies but before you've spent significant money on branding, prototypes, or legal fees. It's a 'pre-business plan' checkpoint. Many founders waste months perfecting a pitch deck for an idea that a two-week feasibility check would have killed. If your study shows strong potential, its findings become the backbone of your formal business plan.

What's the most overlooked aspect of a feasibility study that can sink a project later?

Operational feasibility. Teams get obsessed with market size and financial projections but gloss over the day-to-day execution. They don't ask: Do we have the right team culture to run this? What new supply chain headaches will this create? Will our current IT systems scream and die? I've seen a manufacturing expansion fail because the study didn't account for the six-month lead time to hire specialized technicians in that region. The plan looked great on paper, but the operational reality was a nightmare.

How detailed should the financial analysis in a feasibility study be?

Detailed enough to show you understand the major cost drivers and revenue levers, but not a full-blown, line-item forecast. Focus on the big five: 1) Major capital expenditures, 2) Key operational costs (like core materials or labor), 3) Realistic revenue projections based on your market analysis, 4) A break-even analysis, and 5) Sensitivity analysis (what if costs are 20% higher or sales are 30% lower?). The goal isn't perfect accuracy; it's to prove the financial model is plausible and identify the biggest financial risks.

Can a feasibility study ever be too positive?

Absolutely, and that's a major red flag. An overly optimistic study is usually a political document, not an analytical one. It's crafted to justify a decision already made. A good study actively hunts for reasons to say 'no.' It challenges assumptions, pressures-tests best-case scenarios, and dedicates equal effort to identifying fatal flaws as it does to highlighting opportunities. If your study doesn't make you at least a little uncomfortable or force you to redesign part of the concept, it probably wasn't rigorous enough.