Key Insights

- What Exactly Is the Quick Ratio? Breaking Down the Jargon

- The Quick Ratio Formula: It's Simpler Than You Think

- How to Interpret Your Quick Ratio Number: What's Good, What's Bad?

- Quick Ratio vs. Current Ratio: What's the Real Difference?

- Actionable Steps: How to Improve Your Company's Quick Ratio

- Common Mistakes and Misconceptions About the Quick Ratio

- Quick Ratio in Action: Questions from the Real World (Q&A)

- Wrapping It Up: The Quick Ratio as Your Financial Pulse Check

Let's talk about a number that can keep business owners and investors up at night. It's not revenue, and it's not profit. It's something more immediate, more pressing. It's the question of whether a company can pay its bills right now if things get tight. That's where the quick ratio comes in. You might have heard it called the acid-test ratio. Same thing. It's one of those financial metrics that sounds complicated but is actually pretty straightforward once you break it down. And honestly, if you're running a business or thinking of investing in one, you can't afford to ignore it.

I remember looking at the books for a small manufacturing company a few years back. Profits looked decent on paper. But when we ran the quick ratio, it was a dismal 0.5. That meant for every dollar of short-term debt, they only had fifty cents in truly liquid assets to cover it. The owner was shocked. All his cash was tied up in inventory that wasn't moving. That number was a red flag we couldn't ignore, and it forced a tough conversation about cash flow management. It's moments like that which really hammer home why this ratio matters.

The Core Idea: The quick ratio strips away all the fluff and asks one brutal question: "If all our short-term creditors demanded payment today, could we pay them without selling a single widget or piece of inventory?" It's a stress test for your liquidity.

What Exactly Is the Quick Ratio? Breaking Down the Jargon

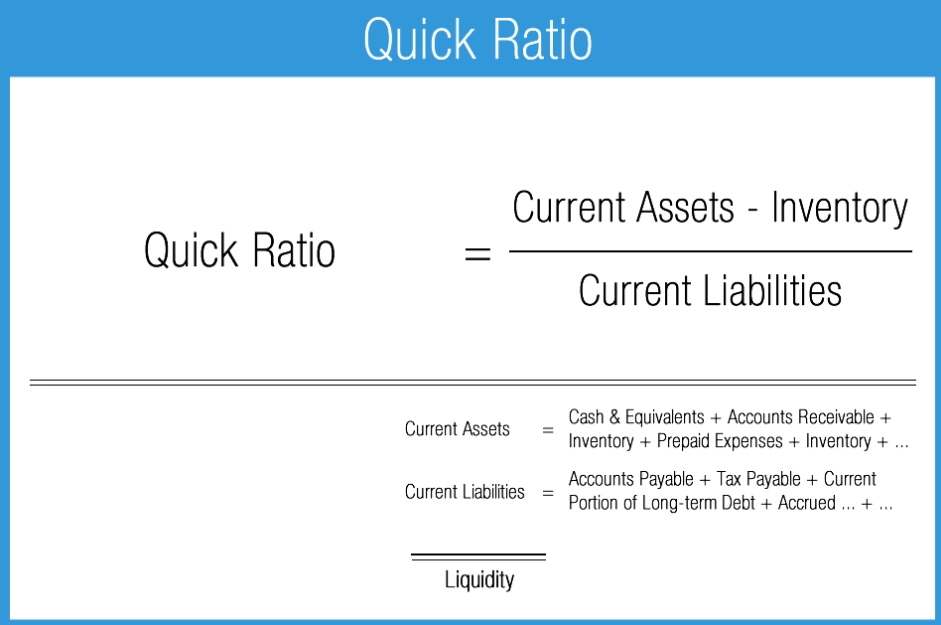

In simple terms, the quick ratio measures a company's ability to pay its current liabilities (debts due within a year) with its most liquid assets. The key word here is liquid. We're not counting everything the company owns. We're only counting the assets that can be turned into cash quickly—typically within 90 days—and without a significant loss in value.

So, what gets included? Primarily three things:

- Cash and Cash Equivalents: This is the obvious one. Physical cash, money in checking and savings accounts. Cash equivalents are super-short-term, highly liquid investments like Treasury bills or money market funds. You can find this line item easily on any balance sheet.

- Marketable Securities: These are investments, like stocks or bonds, that can be sold on a public exchange rapidly. The crucial point is that they must be readily marketable. A long-term strategic investment in another company usually doesn't count.

- Accounts Receivable (Net): This is money owed to the company by its customers for goods or services already delivered. It's considered liquid because, in theory, it converts to cash as invoices are paid. However, you have to use the net figure, which accounts for an estimate of receivables that will never be collected (allowance for doubtful accounts). This is where many amateur analyses go wrong.

And crucially, what's excluded?

Inventory. This is the big one. The quick ratio intentionally leaves inventory out. Why? Because inventory isn't guaranteed to sell quickly or at its recorded value. It might be obsolete, seasonal, or simply not in demand. Selling it in a fire sale to pay debts could mean huge losses. The quick ratio, being the stricter test, assumes you can't rely on it.

Prepaid expenses are also out. You've already paid these (like insurance for the next year). You can't get that cash back to pay a creditor.

The Quick Ratio Formula: It's Simpler Than You Think

Don't let the math scare you. The formula is beautifully simple:

Quick Ratio = (Cash & Cash Equivalents + Marketable Securities + Net Accounts Receivable) / Current Liabilities

All these numbers come straight from the company's balance sheet. Let's walk through a real-world example. Imagine Company XYZ has the following on its balance sheet (in thousands):

- Cash: $50,000

- Short-term Investments (Treasury bills): $20,000

- Accounts Receivable: $100,000

- Allowance for Doubtful Accounts: ($5,000) → So, Net Receivables = $95,000

- Inventory: $150,000

- Total Current Liabilities: $120,000

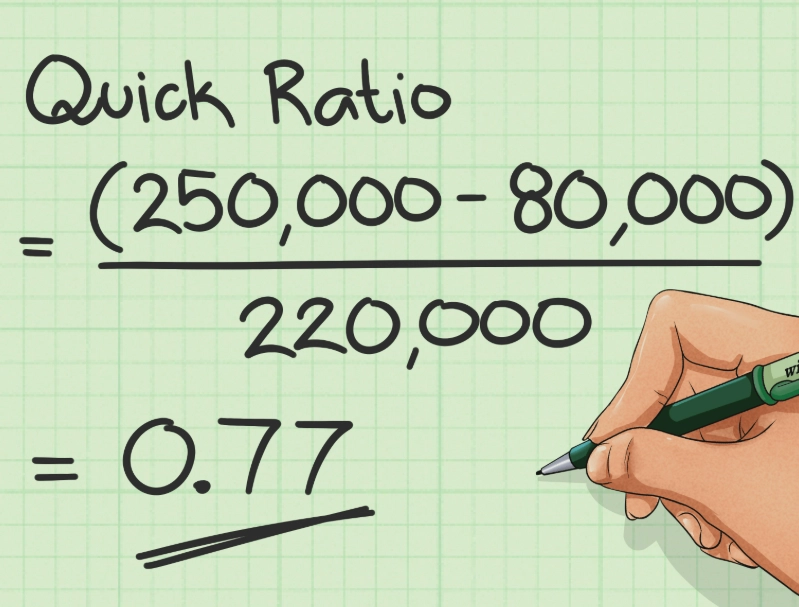

First, sum up the quick assets: $50,000 (Cash) + $20,000 (Investments) + $95,000 (Net Receivables) = $165,000.

Then, plug into the formula: $165,000 / $120,000 = 1.375.

So, Company XYZ's quick ratio is 1.375. For every dollar of short-term debt, it has $1.38 in liquid assets to cover it. That's generally seen as a comfortable position.

Pro Tip: Always check the notes to the financial statements. Sometimes what a company classifies as a "short-term investment" might not be as liquid as you think. Transparency is key. For authoritative guidance on what constitutes a liquid asset, the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) provides the standards that companies follow.

How to Interpret Your Quick Ratio Number: What's Good, What's Bad?

This is where context is everything. A quick ratio of 1.0 is the classic benchmark. It means liquid assets exactly equal current liabilities. The company could, in theory, pay off all its short-term debts immediately without touching inventory.

But the world isn't that black and white.

A quick ratio significantly above 1 (say, 2.0 or 3.0) indicates strong liquidity. Creditors and investors love this. It suggests a large safety cushion. However, there's a downside. It can also signal that the company is hoarding too much cash or isn't efficiently using its assets to grow (e.g., by reinvesting in the business or paying dividends). Excess cash earns a paltry return.

A quick ratio below 1 is the danger zone. It means the company doesn't have enough liquid assets to cover its short-term obligations. It would need to sell inventory, generate more cash from operations, or secure financing to avoid a liquidity crunch. A ratio of 0.5, like in my earlier example, is a major warning sign.

But here's the critical part: The "ideal" quick ratio varies wildly by industry. This is the mistake I see most often. Applying a one-size-fits-all standard will lead you astray.

| Industry | Typical Quick Ratio Range | Why It's Like That |

|---|---|---|

| Technology / Software (SaaS) | 1.5 - 3.0+ | Often subscription-based with low physical inventory, high receivables, and a need for a cash buffer for R&D. |

| Retail | 0.2 - 0.8 | Inventory is lifeblood and turns over very quickly (days/weeks). They operate on thin margins and rely on fast inventory conversion to pay suppliers (like Walmart's famous model). A high quick ratio here might mean poor inventory management. |

| Services (Consulting, Legal) | 1.0 - 1.8 | Little to no inventory. Assets are mostly cash and receivables. Liabilities are often accrued expenses and deferred revenue. |

| Manufacturing | 0.7 - 1.2 | Holds significant raw material and finished goods inventory. The quick ratio will naturally be lower than the current ratio. The key is the trend and the cash conversion cycle. |

You see the difference? A quick ratio of 0.7 would be a crisis for a software firm but might be perfectly normal for a large retailer. Always compare a company's quick ratio to its direct competitors and its own historical trend. The Federal Reserve's data on assets and liabilities of commercial banks can provide useful benchmarks for the financial sector, for instance.

Watch Out: A "good" quick ratio can be manipulated, or at least painted in a favorable light, near the end of a reporting period (window dressing). A company might delay paying its own bills to keep cash high, or aggressively collect receivables. Looking at the trend over several quarters is more telling than a single snapshot.

Quick Ratio vs. Current Ratio: What's the Real Difference?

This causes a lot of confusion. The current ratio is the quick ratio's more lenient cousin. Its formula is:

Current Ratio = Total Current Assets / Total Current Liabilities

The key difference? The current ratio includes inventory and prepaid expenses in the numerator.

Let's go back to Company XYZ. Its total current assets were: $50,000 + $20,000 + $100,000 + $150,000 = $320,000. Current liabilities were $120,000.

Current Ratio = $320,000 / $120,000 = 2.67

Compare that to its quick ratio of 1.38. That's a huge gap, driven entirely by that $150,000 in inventory.

Which one should you use? Both, but for different reasons.

- Use the current ratio for a general overview of working capital health. It's a good starting point.

- Use the quick ratio when you want a conservative, worst-case scenario analysis. It's the stricter test of immediate liquidity. Creditors, especially banks, pay very close attention to the quick ratio when assessing credit risk. If you're in an industry where inventory can become obsolete fast (tech hardware, fashion), the quick ratio is far more important.

Personally, I always look at both. A strong current ratio paired with a weak quick ratio tells me the company's liquidity is heavily dependent on inventory—a potential risk factor.

Actionable Steps: How to Improve Your Company's Quick Ratio

So, you've calculated your quick ratio and it's lower than you'd like. Don't panic. Improving it comes down to two levers: increasing your quick assets or decreasing your current liabilities. Here are some practical strategies, ranked from what I've seen work most effectively:

- Accelerate Accounts Receivable Collection. This is usually the lowest-hanging fruit. Invoice immediately, offer small discounts for early payment, and implement a rigorous follow-up process for overdue accounts. Tighten your credit policies for new customers.

- Manage Inventory More Efficiently. While inventory doesn't directly affect the quick ratio, the cash you free up from reducing excess stock flows into your cash balance (a quick asset). Implement Just-In-Time (JIT) systems, identify slow-moving items, and improve demand forecasting.

- Build a Cash Reserve. This sounds obvious but requires discipline. Reinvest profits strategically, but earmark a portion for your liquidity buffer. Treat it as a non-negotiable operational expense.

- Re-negotiate Terms with Suppliers. Can you extend your accounts payable period from 30 to 45 or 60 days? This reduces current liabilities. Be careful not to damage important supplier relationships.

- Convert Non-Liquid Assets. Do you have old equipment or non-core investments that can be sold? The cash influx boosts the numerator.

- Refinance Short-Term Debt. If you have a short-term loan coming due, see if you can refinance it into a longer-term loan. This moves the liability from "current" to "long-term," taking it out of the quick ratio denominator.

Improving your quick ratio isn't about accounting tricks; it's about fundamentally better working capital management. It takes time and consistent effort.

Common Mistakes and Misconceptions About the Quick Ratio

Let's clear the air on a few things I see people get wrong all the time.

Mistake 1: Treating all Accounts Receivable as equal. A $100,000 receivable from a Fortune 500 company is not the same as $100,000 from a startup that might fail. The quality of receivables matters enormously. Always use the net figure.

Mistake 2: Ignoring the industry context. As we discussed, chanting "must be above 1" is useless. A deep dive into industry norms is essential. Resources like business analysis from major financial publications often discuss sector-specific liquidity challenges.

Mistake 3: Looking at a single point in time. Finance is a movie, not a snapshot. Is the quick ratio improving or deteriorating over the last 8 quarters? What's the trend? A declining trend is a problem even if the absolute number still looks okay.

Mistake 4: Forgetting about off-balance-sheet obligations. The quick ratio only uses what's on the balance sheet. It doesn't account for unused lines of credit (which provide liquidity) or potential litigation liabilities (which could become current). You need to read the footnotes.

Mistake 5: Over-optimizing for a high number. Chasing a sky-high quick ratio can mean you're not taking smart risks to grow the business. It's about balance—having enough of a cushion without being stagnant.

Quick Ratio in Action: Questions from the Real World (Q&A)

Here are some specific questions I've been asked over the years that get to the heart of how people use this metric.

Q: Is a quick ratio that's too high a bad thing?

A: It can be, yes. It's a sign of inefficiency. Think of cash as a tool. If you have a massive pile of it sitting in a checking account earning 0.01% interest, you're not putting that tool to work. That money could be reinvested in marketing, new equipment, R&D, or returned to shareholders. A persistently high quick ratio warrants asking: "Is management too risk-averse? Are they missing growth opportunities?"

Q: How do I analyze the quick ratio for a startup that's burning cash?

A: This is a special case. For a pre-revenue or early-revenue startup, the quick ratio will look bizarre. They may have high cash (from venture funding) and very low current liabilities (few suppliers). The ratio might be 5.0 or higher. Here, the quick ratio is less useful on its own. The critical metric becomes the cash runway: how many months of operations can that cash cover? You're watching the burn rate against the cash balance. The quick ratio only tells part of that story.

Q: Can the quick ratio be negative?

A: Mathematically, no, because assets are positive numbers. But if a company has negative working capital (current liabilities exceed current assets), its quick ratio will be less than 1.0. In a dire situation where cash and receivables are negligible, it can approach zero. That's a five-alarm fire.

Q: As an investor, how should I use the quick ratio?

A: Use it as a filter for solvency risk. I would be very hesitant to invest in a company with a quick ratio below 0.5 unless there's a very compelling, industry-specific reason and a clear plan to fix it. Compare it to the company's main competitors. Look for stability or improvement over time. A sudden, unexplained drop in the quick ratio is a major red flag that deserves investigation—perhaps they made a big sale on lousy credit terms, or a major receivable went bad.

Wrapping It Up: The Quick Ratio as Your Financial Pulse Check

At the end of the day, the quick ratio isn't the be-all and end-all of financial analysis. No single metric is. But it is an incredibly powerful, focused tool. It cuts through the complexity and gives you a clear, conservative read on a company's immediate financial resilience.

Whether you're a business owner steering your ship, a manager assessing your department's health, or an investor sizing up a potential opportunity, make the quick ratio a regular part of your review. Calculate it. Understand what goes into it. Compare it properly. And most importantly, use the insight it provides to ask better questions and make more informed decisions.

Because in business, the question isn't always about making money. Sometimes, it's simply about surviving long enough to do so. And that's exactly what a solid quick ratio helps you ensure.