Let's talk about a hundred dollars. Not a lot, not a little. Imagine it lands in your bank account unexpectedly—a small bonus, a tax refund, a gift. What happens next? Do you immediately think about that new pair of shoes, a nice dinner out, or putting it towards the credit card bill? Your split-second reaction to that extra cash is more than just a spending habit; it's a core economic concept with a fancy name: your marginal propensity to consume, or MPC.

Most explanations stop at the dry definition: the fraction of an extra dollar of income that a person consumes. But that's like describing a car engine by listing its parts without explaining how it makes the car move. The real power of understanding MPC isn't in passing an economics exam; it's in decoding your own financial behavior, predicting how policies will hit your wallet, and seeing the invisible threads that connect millions of individual spending decisions to the health of the entire economy.

I've seen too many people get this wrong. They treat MPC as a fixed, universal number, which leads to bad personal budgets and, frankly, some pretty ineffective government policies. Let's dig into what it really means.

What You'll Learn in This Guide

MPC Demystified: It's Not What You Think

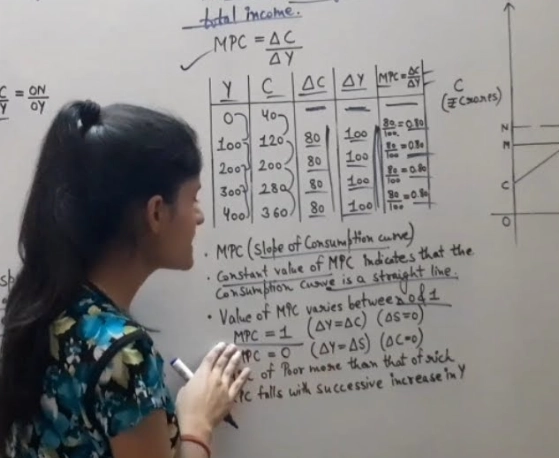

The textbook says MPC is the change in consumption divided by the change in disposable income. Fine. But here's the nuance everyone misses: your MPC depends entirely on where you are financially.

The Big Idea: MPC isn't one number for a person or a country. It's a relationship that shifts with income level, economic confidence, and even the type of windfall. A billionaire's MPC on an extra million is near zero. A family living paycheck-to-paycheck? Their MPC on an extra $500 might be 0.9 or even 1.0—every cent gets spent on rent, groceries, or overdue bills.

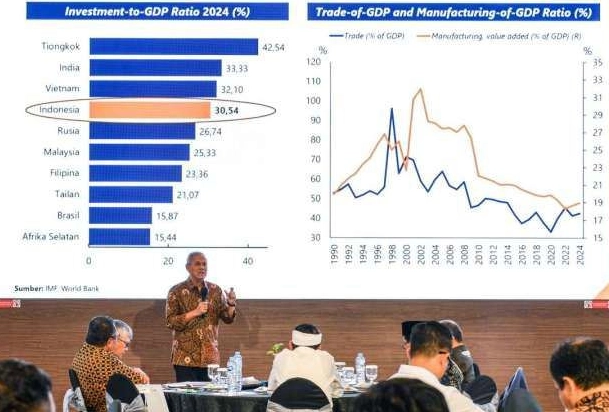

This is why the common assumption of a "national MPC" is so flawed. When policymakers design a tax cut, it matters profoundly whether that money goes to high earners (low MPC, likely saved) or low-to-middle earners (high MPC, quickly spent back into the economy). The Congressional Budget Office and the Federal Reserve analyze these distributional effects closely, though public debate often glosses over them.

The MPC of Different Income Groups: A Reality Check

Look at this breakdown. It's not exact for every person, but it reflects a well-documented economic pattern.

| Income Group | Estimated MPC Range | Where the Extra Dollar Likely Goes |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Income / Financially Strained | 0.9 – 1.0 | Essential goods (food, utilities, fuel), paying down high-interest debt. |

| Middle-Income | 0.6 – 0.8 | Mix of essentials, discretionary spending (dining out, upgrades), and some saving. |

| High-Income / Wealthy | 0.2 – 0.4 | Primarily saved or invested; consumption is largely unaffected by marginal income. |

See the gap? This table explains why uniform economic policies have uneven effects. A stimulus check has a much bigger economic "bang for the buck" when sent to the first group compared to the last.

How to Calculate Your Own MPC (The Right Way)

Want to know your number? Don't just guess. Here's a practical method that beats any online calculator.

Step 1: Pick a windfall. Think of the last time you received unexpected income. A work bonus, a freelance payment, a gift. The amount should be noticeable but not life-changing—say, between $200 and $5,000.

Step 2: Track the aftermath. How much of that specific money did you spend within, say, two months? Be honest. Did you buy something you'd been postponing? Did you use it for groceries you would have bought anyway? That's consumption. The rest you saved or invested.

Step 3: Do the math. MPC = (Spending from the windfall) / (Total windfall).

My tip: Most people overestimate their self-control. They plan to save a bonus but end up spending most of it. That's not a moral failing; it's human nature and a high MPC in action. Tracking this honestly is the first step to managing it. If your MPC is consistently 0.8 or above, your savings plan might be based on an unrealistic assumption about your future behavior.

Let's say you got a $1,000 bonus. You paid off $300 of credit card debt (that's consumption—it's using income to clear a past consumption liability), spent $400 on a new TV, and put $300 into your savings account.

Your spending from the windfall is $300 + $400 = $700.

Your MPC = $700 / $1,000 = 0.7.

This number is a tool, not a grade. A 0.7 MPC isn't "bad." It's information.

Why MPC is the Secret Engine of the Economy

This is where MPC gets powerful. It's the core component of the spending multiplier. The basic idea: one person's spending becomes another person's income, who then spends a part of it (based on their MPC), and so on.

The formula for the simple multiplier is 1 / (1 - MPC). If the average MPC in the economy is 0.75, the multiplier is 1 / (1 - 0.75) = 4. A $1 billion government infrastructure project doesn't just add $1 billion to the economy; theoretically, it could generate $4 billion in total economic activity as the money circulates.

But here's the expert catch everyone glosses over: the multiplier isn't instant or guaranteed. It assumes the extra spending is on domestically produced goods and services, that there are idle resources (unemployed workers, unused factory capacity), and that confidence is high. If people are fearful (like in a deep recession), they might save the money instead, breaking the chain. This is why stimulus sometimes feels like pushing on a string.

Policymakers at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and central banks spend enormous energy trying to estimate these "marginal propensities" across different groups to forecast the impact of their decisions. They know a tax rebate aimed at low-income families will have a higher multiplier effect than a corporate tax cut.

Using MPC for Smarter Personal Finance, Not Just Theory

Forget the GDP for a second. Your MPC is a diagnostic tool for your financial health.

A consistently high MPC (above 0.9) is a flashing warning light. It means almost every extra dollar you earn is immediately spent. You have no buffer. An unexpected car repair or medical bill becomes a crisis. Your financial life is reactive, not proactive. The goal here isn't to lower your MPC out of shame; it's to build a small emergency fund. Once you have even $1,000 set aside, your MPC on the next windfall will naturally drop because your mind is no longer in scarcity mode.

A very low MPC (below 0.2) isn't automatically "good." It can signal excessive frugality or a disconnect between saving and life enjoyment. Are you saving for a specific, exciting goal (a house, early retirement), or are you just hoarding money out of anxiety? Money is a tool. If you never use the tool, what's the point? Sometimes, consciously deciding to raise your MPC on a bonus for a meaningful experience is the financially intelligent choice.

The sweet spot for most people building wealth is a managed MPC. You automatically save/invest a portion of every raise (a low MPC on future income increases) while allowing a portion for lifestyle improvement. This is the concept of "pay yourself first" in action—it mechanically lowers your effective MPC on total income.

A Real-World Case Study: Stimulus Checks and MPC in Action

Let's look at a recent example. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the U.S. government issued direct Economic Impact Payments (stimulus checks) to most households.

Researchers were able to study MPC in real-time. What did they find? Reports from sources like the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) indicated that MPCs from these checks were notably high, especially among lower-income recipients. A significant portion was spent on essentials within weeks. This high MPC was precisely why this policy tool was chosen: to provide immediate support and prop up consumer demand during a sudden stop in economic activity.

However, the studies also showed variation. Higher-income recipients, who were less financially impacted, had a much lower MPC, saving or investing more of the money. This validates the core principle: MPC is contextual. The same policy (a $1,400 check) had different effects because the underlying MPC of the recipients differed based on their financial circumstances and needs at that moment.

The lesson for any future policy debate? Targeting matters. The economic boost is maximized when support is directed to those with a high marginal propensity to consume.

Your MPC Questions, Answered

So, the next time you get a little extra cash, pause for a second. That decision—spend or save—is a tiny economic event. Understanding your marginal propensity to consume turns that decision from a reflex into a choice. It connects your personal finances to the vast machinery of the national economy. And that's a perspective worth more than a hundred dollars.