Navigate This Guide

- Why Bother? The Real-World Stakes of Getting Contingency Right

- Contingency in the Wild: How Different Fields Use the Idea

- From Concept to Action: Building a Contingency Plan That Doesn’t Suck

- Contingency Theory: The Academic Backbone

- Answering Your Burning Questions About Contingency

- Wrapping It All Up: A Contingent Mindset

You've probably heard the word thrown around in meetings, seen it in project documents, or maybe your boss just told you to "prepare for contingencies." And you nodded, but a tiny part of you wondered, "Okay, but what are we really talking about here?" It's one of those business-y words that sounds important but can feel a bit fuzzy around the edges.

Let's clear that up right now. At its absolute core, to define contingency is to talk about something that might happen. It's an event or a circumstance that is possible but not certain. It's the "if" in your sentence. If the server crashes. If the key supplier goes bankrupt. If it rains on the day of the outdoor product launch. That possibility, that conditional event—that's the contingency.

But here's where it gets interesting, and honestly, where most quick definitions stop short. Calling it just a "possible event" is like calling a Swiss Army knife just a "sharp thing." It misses the entire point of why the concept is so powerful. The real weight of contingency isn't in the event itself; it's in our response to its possibility. The moment you acknowledge a contingency, you're forced out of a simple, linear view of the world. You have to start thinking in branches, in probabilities, in "what-ifs."

The Nutshell Definition: A contingency is a future event or condition that is possible but uncertain, and whose occurrence would have a significant impact, requiring a prepared response or plan.

I remember working on a big client launch years ago. Our plan was perfect. Timeline? Meticulous. Budget? Approved. Then, two days before go-live, the main developer came down with a nasty flu. That was our contingency—the one we'd vaguely acknowledged but hadn't truly planned for. We scrambled, the launch was messy, and I learned the hard way that understanding contingency is useless without the "plan" part that usually follows it.

Why Bother? The Real-World Stakes of Getting Contingency Right

Why spend time splitting hairs over a definition? Because how you define contingency in your mind directly shapes how you operate. If you see it as a rare, catastrophic "act of God," you'll prepare one way (maybe you won't prepare at all). If you see it, more accurately, as a normal part of a complex system—the predictable unpredictability of life and business—you'll build differently.

Think about it. A startup ignoring cash flow contingencies might burn out before its first customer. A construction project without weather contingencies will blow its schedule. Your weekend BBQ without a rain plan turns into a soggy disaster. The scale changes, but the principle doesn't.

The biggest mistake isn't failing to predict the exact event; it's failing to accept that something unpredictable will happen. The value of contingency thinking is in building systems that are resilient, not clairvoyant.

It's the difference between being reactive and being resilient. One leaves you at the mercy of events. The other gives you a fighting chance.

Contingency in the Wild: How Different Fields Use the Idea

This isn't just a business buzzword. The concept of contingency pops up everywhere once you know to look for it, and each field adds its own twist. Understanding these angles gives you a much richer, 3D view of the term.

Business & Project Management: The Plan in the Drawer

This is where most of us collide with the term. Here, contingency is almost always paired with "plan" or "fund."

- Contingency Plan: A pre-defined set of actions to be taken if a specific risk materializes. It answers "What will we do if this happens?" For example, a data center's contingency plan for a power outage switches operations to a backup generator and a secondary site. The U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) provides extensive frameworks for contingency planning for disasters, which businesses can adapt.

- Contingency Fund (or Reserve): A pile of money set aside specifically for unforeseen costs. It's not for scope changes you already want; it's for the stuff you didn't see coming. A common rule of thumb is 10-15% of a project's budget, but that can vary wildly.

In business strategy, contingency thinking challenges the idea of a single, perfect, forward-marching plan. It argues for flexibility and options.

Philosophy & Logic: It Depends...

Philosophers love this stuff. Here, contingency is the opposite of necessity. A necessary truth is one that must be true (like 2+2=4). A contingent truth is one that happens to be true but could have been otherwise. "It is raining in London right now" is contingent—it's true or false based on conditions, not logic.

This might seem abstract, but it's profound. It grounds the idea that much of our world is not pre-determined. Things could be different. This philosophical underpinning is why contingency is linked to freedom, chance, and possibility.

Law & Contracts: The Fine Print That Matters

Ever skimmed a contract and seen a clause that starts with "In the event of..." or "Should Party A fail to..."? That's a contingency clause. It outlines what happens under specific, non-guaranteed future conditions.

- Contingency Fee: A lawyer's payment that is contingent on winning the case (common in personal injury law). No win, no fee.

- Contingency in Real Estate: An offer on a house that is contingent on the buyer selling their current home, or on a satisfactory inspection report. It makes the deal conditional.

The legal system runs on defining these conditional outcomes clearly to avoid disputes when the unexpected occurs.

Psychology & Behavior: The Situational You

Contingency theory in leadership and psychology argues that there's no single best way to lead, manage, or behave. The most effective approach is contingent upon the situation. The right leadership style depends on (is contingent on) the task, the team's maturity, the urgency, etc.

It's a rejection of one-size-fits-all solutions. Sound familiar? It's the same core idea: the best response depends on the specific circumstances that arise.

This psychological angle is the one I find most humbling. It reminds me that my go-to management style won't work for every person or every problem. I have to be contingent in my own thinking, which is harder than it sounds.

From Concept to Action: Building a Contingency Plan That Doesn’t Suck

Alright, so we've defined contingency from every angle. Now what? How do you move from understanding to doing? Let's talk about the contingency plan. Most guides make this sound like a bureaucratic slog, but it's really just smart thinking written down.

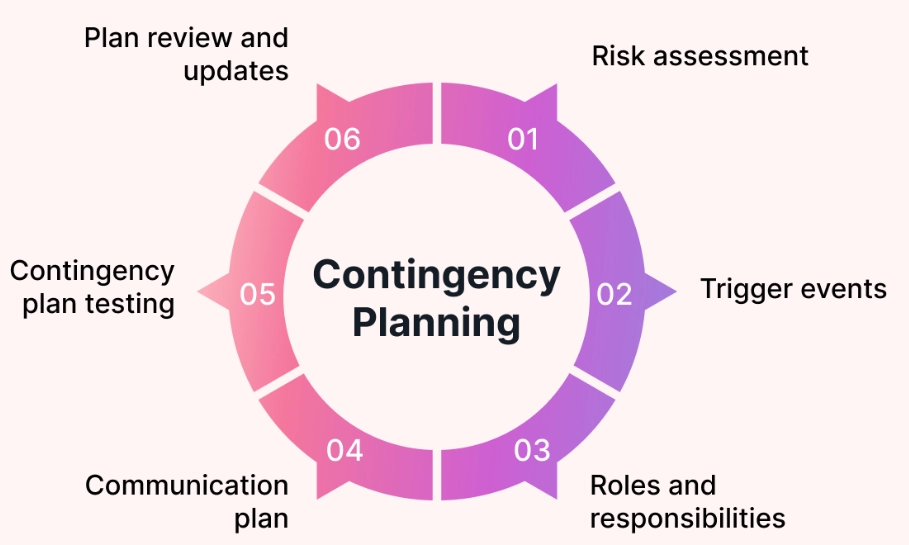

Here’s a breakdown of what goes into a solid plan, moving beyond the basic "identify a risk" step.

| Plan Component | What It Really Means | The Pitfall to Avoid |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger Condition | The specific, observable event that says "the contingency is happening NOW." (e.g., "Website downtime exceeds 5 minutes," not "if something goes wrong"). | Vague triggers. If no one knows when to activate the plan, it won't get activated. |

| Immediate Response Actions | The first 5-6 things to do, in order, to stabilize the situation. Assign these to specific people by name. | Assuming people will know what to do. Panic makes brains fuzzy. Write it down. |

| Communication Protocol | Who needs to be informed, in what order, and what is the key message? (Team lead? CEO? Clients?) | Radio silence or chaotic, conflicting messages that make the situation worse. |

| Decision-Making Authority | Who is in charge during the contingency? Is it the same as the project manager? Often it shouldn't be. | Confusion over who can make a critical spending or pivot decision when time is short. |

| Fallback & Recovery Steps | How do we move to a backup system? How do we restart operations? What's the minimum viable service? | Only having a "stop" plan without a "restart" plan. The goal is continuity, not just shutdown. |

| Review & Update Point | After the dust settles, when will we review what happened and update the plan? This step is almost always skipped. | Treating the plan as a static document. If you don't learn and update, your next plan will be just as flawed. |

The table looks neat, but let me be honest—the first plan you write will feel clunky. You'll miss things. That's okay. The act of thinking through the columns is 80% of the benefit. It forces the team to have the hard conversations before the pressure is on.

A word of caution: Don't let perfect be the enemy of good. A one-page plan for your top three risks that everyone has read is infinitely better than a 50-page master document that's buried in a shared drive no one remembers.

Contingency Theory: The Academic Backbone

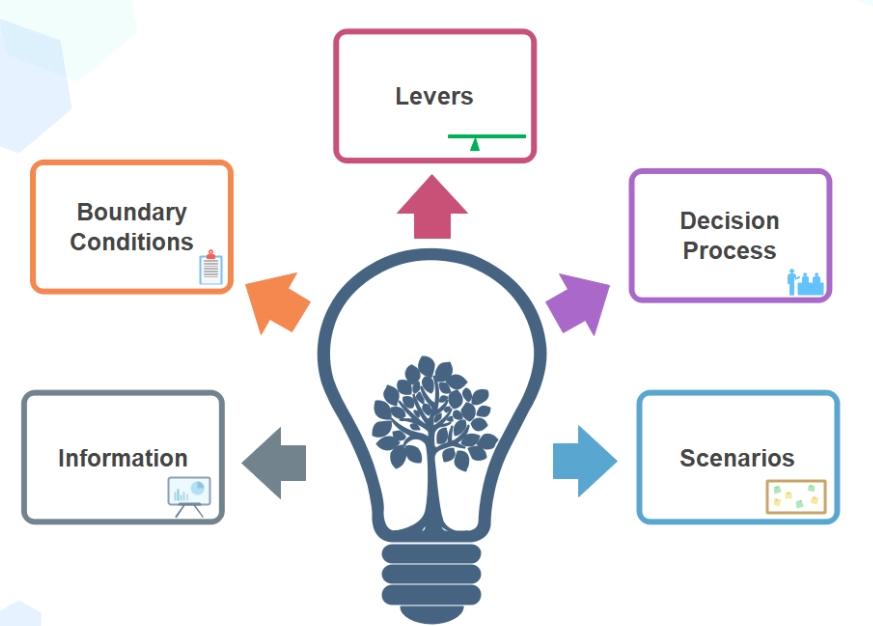

If you really want to dig deeper, you'll bump into Contingency Theory. This isn't about making plans; it's a whole framework for understanding organizations. Developed in the 1960s and 70s by folks like Joan Woodward, Tom Burns, and others, it was a direct challenge to the idea of "one best way" to organize a company (looking at you, classic scientific management).

The theory's core argument is simple but powerful: The optimal organization structure is contingent upon various internal and external factors.

What factors? Think about:

- Environment: Is it stable and predictable (like a utility company) or dynamic and chaotic (like a tech startup)? Stable environments might suit hierarchical structures; chaotic ones need flatter, more adaptive forms.

- Technology: The complexity of the technology used shapes how teams need to coordinate.

- Size: What works for a 10-person team breaks down at 1000 people.

- Strategy: A strategy focused on cost-leading efficiency needs a different setup than one focused on innovation.

This theory explains why copying another company's "awesome" management structure might fail miserably for you. Your contingencies are different. The Project Management Institute (PMI) often discusses contingency-based approaches within its frameworks, acknowledging that project management methodology must also be contingent on project specifics.

Answering Your Burning Questions About Contingency

Answering Your Burning Questions About Contingency

Is a contingency the same as a risk?

Great question, and a common point of confusion. They're close cousins but not twins. A risk is the broader potential for something to go wrong (or right). It's often expressed as a probability and an impact. Contingency is more specific—it's a defined, uncertain future event that you can point to, and more importantly, the plan you have for it. You manage risks; you execute a contingency plan. Think of risk as the field of play, and contingencies as the specific plays you've practiced for key scenarios.

How much contingency fund is enough?

Oh, the million-dollar question (literally). There's no magic number, and anyone who gives you one without context is oversimplifying. It depends on (see, contingency again!) the project's complexity, novelty, duration, and your organization's risk tolerance. A simple, repeatable project might need 5%. A groundbreaking, first-of-its-kind project in a volatile market? 25% or more might be prudent. The key is to base it on your identified risks, not just a blanket percentage. Do a quantitative risk analysis, add up the probable costs of your top risks, and that's a more defensible starting point for your fund.

What's the biggest pitfall in contingency planning?

Complacency after the plan is written. People treat the plan like a fire extinguisher—put it on the wall and forget about it. But businesses and projects evolve. The contingency you planned for in month one might be irrelevant by month six, while two new big risks have emerged. The plan becomes a stale, feel-good document that provides zero real protection. You must schedule regular reviews, at least quarterly, to ask: "Are our triggers still right? Are the assigned people still here? Do our responses still make sense?"

Can you over-plan for contingencies?

Absolutely, yes. This is called "analysis paralysis" or over-engineering. You can spend so much time and resources planning for every remote possibility that you never actually execute the main project. You burn your budget on plans instead of action. The goal is not to eliminate all surprise—that's impossible. The goal is to be robust enough to handle the most likely and most impactful surprises without derailing completely. It's a balance. I've seen teams waste weeks on elaborate plans for events with a 1% chance of happening, while ignoring the 40%-chance events staring them in the face.

Pro Tip: Use the "Probability/Impact Matrix." Focus your detailed contingency planning on the events in the high-probability/high-impact and low-probability/high-impact boxes. For low-impact stuff, even if it's high-probability, a simple, lightweight response plan is enough.

Wrapping It All Up: A Contingent Mindset

So, after all this, how should we define contingency in a way that's actually useful? Forget the dictionary for a second.

Think of contingency as an acknowledgment of reality. It's the operational recognition that the future is a set of possibilities, not a single predetermined track. It's the bridge between your optimistic main plan and the messy, unpredictable world where that plan has to live.

The strength of a plan is not measured by how closely it's followed, but by how gracefully it adapts when it can't be.

Building contingency plans—and more importantly, fostering a contingent mindset—isn't about being pessimistic. It's the opposite. It's about being confident enough to look at the uncertainties head-on and say, "We've thought about that. We have a move." It reduces anxiety and enables decisive action when things get weird.

Start small. Pick one active project. Gather the team for 30 minutes and ask: "What's the one thing that could happen in the next month that would really throw us off? Okay, what would our first three steps be if that happened?" Write those steps down. Share them. You've just built your first, most valuable contingency plan.

The goal isn't to create a perfect, unbreakable system. The goal is to be less fragile. And now, you have the tools to start.