Key Highlights

- The Five Non-Negotiable Pillars of a Perfectly Competitive Market

- Putting Theory to the Test: Where Do We See This in the Wild?

- Why Bother? The Good, The Bad, and The Efficient

- How It Stacks Up: The Market Structure Lineup

- Clearing the Fog: Your Perfect Competition Questions Answered

- The Bottom Line: Why This "Unrealistic" Idea Matters to You

Let's talk about perfect competition. You've probably heard the term thrown around in econ classes or maybe in a business article, and it sounds, well, perfect. But what does it actually mean on the ground? It's one of those foundational ideas that feels theoretical—almost like a thought experiment—but understanding it changes how you see everything from the price of milk to why some tech giants seem untouchable.

I remember first learning about it and thinking it was a neat, tidy model that had little to do with the messy real world. But that's exactly the point. It's a benchmark, a north star. By defining what a perfectly competitive market looks like, we get a ruler to measure everything else against. It helps us ask better questions: Why isn't this market working like the textbook says? What's getting in the way? And is that a good or a bad thing?

At its heart, perfect competition describes a market structure where no single buyer or seller has any power to influence the price. The price is just... out there. It's determined by the entire market—all the supply meeting all the demand. Think of it as economic democracy in its purest form.

It's not about companies being perfect or products being flawless. Far from it. It's about the structure of the market itself creating certain outcomes. And those outcomes are pretty specific: lots of efficiency, zero long-term profit for producers, and prices that just cover the cost of making the next unit. Sounds thrilling, right? Well, it's crucial.

The Five Non-Negotiable Pillars of a Perfectly Competitive Market

For a market to be labelled as having perfect competition, economists agree it must check off five very specific boxes. Miss one, and you're in a different model—like monopolistic competition, oligopoly, or monopoly. Here’s the checklist that creates this unique economic environment.

A Crowd of Buyers and Sellers

This is the first and most obvious rule. We're not talking about a dozen farmers at a roadside stand. We're talking about a huge number. So many that if Joe the Wheat Farmer decides to pack up and go home, or if Mega-Bakery needs ten truckloads more, the total market supply and demand don't even blink. The individual is a drop in the ocean. This completely strips away any potential for bullying or price-setting by a single player.

Ever tried to haggle over the price of a single share of Apple stock? You can't. You take the market price or you leave it. That's the vibe.

The Identity Crisis: Homogeneous Products

In a perfectly competitive market, every seller's product is identical to every other seller's product. A bushel of No. 2 hard red winter wheat from Kansas is a bushel of No. 2 hard red winter wheat from Kansas. It's graded and standardized. There are no brands, no logos, no "farm-fresh" marketing claims that make one seller's wheat meaningfully different from another's.

This homogeneity means competition can only be about price. You can't convince someone to pay more because your wheat is shinier or comes in a better bag. If you charge one cent more than the going market rate, buyers will simply go to the next guy. Instantly.

Perfect Information for Everyone

This one is a real doozy in the age of the internet, but it's still a high bar. The assumption is that all buyers and sellers have complete, free, and instantaneous knowledge of everything relevant: prices, product quality, technology, and profit opportunities. No secrets, no insider trading, no hidden defects.

A buyer knows exactly what every seller is charging. A seller knows exactly what it costs every other seller to produce. This transparency is what makes the market so brutally efficient. If there's a better price or a cheaper production method somewhere, everyone knows and reacts immediately, wiping out any temporary advantage.

Freedom to Come and Go

There are no barriers. No giant moats filled with patents, no huge upfront capital costs, no government licenses blocking the door. If you see farmers making a profit growing soybeans, you can freely use your land to grow soybeans next season. Conversely, if you're losing money, you can just as easily switch to corn or let the field lie fallow.

This free entry and exit is the engine that drives long-run economic profit to zero. Profits act as a signal, attracting new firms until the profit is competed away. Losses act as a signal too, pushing firms out until the remaining ones can at least break even.

The Price-Taker Reality

This is the consequence of all the previous points. In perfect competition, every single firm is a price taker. They look up at the market price, which is determined by the collective intersection of industry supply and demand, and they accept it. Their own individual decisions are too insignificant to move that price needle.

This is the core behavioral difference from a monopoly (a price maker). A wheat farmer doesn't "set" the price of wheat. The global market does. The farmer's only decisions are: "Shall I produce at this price? And if so, how much?"

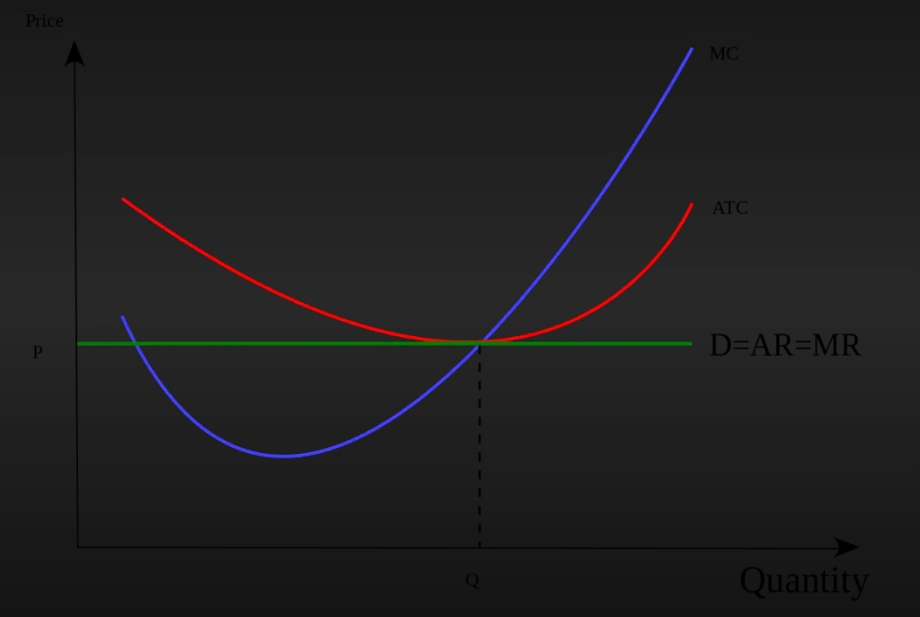

Graphically, this means the demand curve facing the individual firm is perfectly horizontal—a straight, flat line at the market price. Sell one unit or ten thousand units, the price per unit is the same.

Putting Theory to the Test: Where Do We See This in the Wild?

Okay, so that's the pristine theory. Let's be real: finding a market that ticks all five boxes perfectly is like finding a unicorn. The world is messy. But we get close in some places, close enough that the model gives us powerful insights. These are the classic examples you'll hear, and they're useful, even if they're not 100% pure.

The Classic: Agricultural Commodities

This is the go-to example for a reason. Think wheat, corn, soybeans, pork bellies, rough rice. Let's break it down against our checklist:

- Many buyers/sellers? Yes. Thousands upon thousands of farmers and a global array of buyers (food processors, governments, other countries).

- Homogeneous product? Very close. Commodities are graded into standardized classes. No. 2 yellow corn is a fungible good.

- Perfect information? Thanks to commodity exchanges like the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT) and real-time data, price information is highly transparent and global. It's not perfect, but it's remarkably good.

- Free entry/exit? In the long run, relatively. Land can be repurposed, though there are significant time lags and capital costs (not exactly "free").

- Price takers? Absolutely. An individual farmer has no influence on the global price of corn.

It's the closest real-world analog we have, though even here, government subsidies, futures trading, and large agribusinesses introduce wrinkles.

Other markets often get mentioned, but with bigger caveats. The foreign exchange market (Forex) for major currency pairs has many participants and high transparency, but the players aren't all small (central banks are huge), and the product (US Dollars) is unique, not homogeneous with other goods. The market for unskilled labor in a large city has many workers and many employers, but labor is not homogeneous—skills, attitude, and reliability differ.

Why Bother? The Good, The Bad, and The Efficient

So why do economists get so excited about this seemingly unrealistic model? Because it describes an endpoint of maximum efficiency, and that gives us a clear standard for analyzing the costs of market failures.

The Upsides (The "Good" from Society's View)

- Allocative Efficiency (P = MC): This is the big one. In long-run perfect competition equilibrium, the price equals the marginal cost of production. This means resources are allocated in a way that maximizes total societal welfare. The right amount of the good is being produced, and it's going to the consumers who value it most (as shown by their willingness to pay the market price). No waste.

- Productive Efficiency: Firms are forced to produce at the lowest point on their average total cost curve. They must use the least-cost combination of inputs and the most efficient technology available, otherwise they'll be undercut and driven out of business. This minimizes waste in production.

- Consumer is King: With no market power, firms must cater entirely to consumer demand as expressed through price. Innovation (though limited to process innovation to cut costs) ultimately benefits the consumer through lower prices.

The Downsides and Criticisms (The "Bad" or "Boring")

Let's not sugarcoat it. From other perspectives, perfect competition looks pretty bleak.

- Zero Long-Run Profit: This is a nightmare for entrepreneurs and investors. Why take the risk, work the crazy hours, and innovate if the best you can hope for in the long run is to just barely cover all your costs (including a "normal" profit for your own labor and capital)? There's no super-normal profit, no big payoff. It kills the incentive for the kind of groundbreaking, high-risk innovation that drives progress.

- No Product Variety: Homogeneous products mean no choice. You get wheat. Not organic stone-ground wheat, not fortified vitamin wheat—just wheat. The model has no room for differentiation, which is a huge part of what makes modern economies interesting and responsive to diverse consumer tastes.

- No Economies of Scale: The model assumes firms are small. It ignores the potential benefits of large-scale production that can drastically lower costs (think car manufacturing or semiconductor plants). Sometimes, bigness is efficient.

- It's Mostly Theoretical: The most common critique is that it's an ivory tower concept. The strict assumptions almost never hold completely in reality, which can make it feel frustratingly abstract.

I used to think this last point made the model useless. But a map isn't useless because it's not the territory. It's a guide. The model of perfect competition is our map for efficiency.

How It Stacks Up: The Market Structure Lineup

You can't understand perfect competition in a vacuum. Its true value is as the starting point on a spectrum. Let's see how it compares to its more common, less "perfect" cousins. This table lays it out.

| Feature | Perfect Competition | Monopolistic Competition | Oligopoly | Monopoly |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Sellers | Very Many | Many | Few | One |

| Product Nature | Identical (Homogeneous) | Differentiated | Identical or Differentiated | Unique (No close substitutes) |

| Barriers to Entry | None | Low | High | Very High (Blockaded) |

| Firm's Control Over Price | None (Price Taker) | Some (Price Maker within a range) | Significant (Interdependent) | Substantial (Price Maker) |

| Real-World Examples | Agricultural commodities, forex (approx.) | Restaurants, clothing brands, hairdressers | Mobile networks, commercial airlines, auto makers | Local utilities (water, grid), patented drugs (temporarily) |

| Long-Run Profit | Zero Economic Profit | Zero Economic Profit | Can be Positive | Can be Positive |

Looking at this, you can see perfect competition is the extreme of "many" and "no power." As you move right, markets get more concentrated, products get more distinct, and firms gain more control over their destiny (and their prices).

Clearing the Fog: Your Perfect Competition Questions Answered

The Bottom Line: Why This "Unrealistic" Idea Matters to You

Perfect competition isn't just a chapter in Econ 101 to be memorized and forgotten. It's a lens. When you hear about antitrust lawsuits against big tech, the debate is often framed around how far those companies have strayed from a competitive ideal and what the cost of that is. When you wonder why your electricity bill is regulated but your restaurant choice isn't, it's because we perceive one market as a natural monopoly (the opposite of perfect competition) and the other as healthily competitive.

It teaches us that structure determines behavior, and behavior determines performance. A market with many small players, identical products, and easy entry will behave in a profoundly different way than a market with a few giants.

Is the model perfect? No. But as a tool for understanding the forces that shape the prices you pay, the choices you have, and the policies that govern your economy, it's pretty indispensable. It starts the conversation, and that's what a good foundational model should do.