In This Guide

You hear about GDP all the time. On the news, in political debates, in reports about recessions or booms. It's this giant, all-important number that supposedly tells us how a country is doing. But have you ever stopped and wondered, how do you actually compute GDP? Where does that number come from? It's not like someone goes out and counts every single transaction in an economy (imagine trying to do that!).

I remember first learning about this in an economics class. The professor threw up a formula on the board, said "this is GDP," and moved on. It felt like magic. But later, when I tried to understand why one country's economy was growing and another's was shrinking, I realized the "how" behind the number is everything. The method tells a story. And honestly, some of the official explanations out there make it seem more complicated than it needs to be.

So let's break it down. Forget the textbook jargon for a minute. Computing GDP is essentially about adding up the total value of all the "stuff"—goods and services—a country produces in a year. But "value" is tricky. Is it what was spent on it? What was earned making it? Or the value added at each stage? Turns out, you can answer "how do you compute GDP" in three major ways, and if done correctly, they should all get you to roughly the same number. It's like measuring the volume of a swimming pool by counting buckets of water, timing how long it takes to fill, or calculating length x width x depth. Different paths, same destination.

The Three Roads to the Same Number: GDP Calculation Methods

Most people, if they know one way, know the spending approach. It's the famous C+I+G+NX equation. But that's just one side of the coin. In reality, national statistical offices like the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) or the UK's Office for National Statistics use data from millions of sources and cross-check using multiple methods. It's a massive data-crunching exercise. Let's walk through each path.

1. The Expenditure Approach: Following the Money Spent

This is the most intuitive method for a lot of folks. How do you compute GDP using the expenditure approach? You add up all the spending on final goods and services in the economy. Think of it as standing at the checkout counter of the entire nation for a year and ringing up every final sale. The logic is simple: everything produced must be bought by someone (even if that "someone" is a business adding to its inventory).

The formula is the classic one:

Let's unpack what each letter really means, because the definitions matter more than you think.

- C (Consumption): This is the big one, usually 60-70% of GDP in consumer-driven economies like the US. It's household spending on everything: your rent (or imputed rent for homeowners), groceries, Netflix subscription, a new car, a haircut, a doctor's visit. But here's a nuance—it's only spending on final goods. If you buy flour and eggs to bake a cake at home, that's consumption. If a bakery buys flour and eggs, that's an intermediate cost, and we only count the final loaf of bread sold to a customer to avoid double-counting.

- I (Investment): Not what you think. This isn't buying stocks or bonds (that's just swapping financial assets). In GDP-speak, Investment (or Gross Capital Formation) is spending on goods that will be used for future production. It has three main parts:

- Business Fixed Investment: Companies buying machinery, computers, factories, software.

- Residential Investment: Building new houses or apartment buildings. Not buying an existing home (that's just a transfer of an existing asset).

- Change in Private Inventories: This is the sneaky one. If a car company produces $1 billion worth of cars but only sells $900 million, the $100 million sitting in lots is counted as "inventory investment." It's production that hasn't been consumed yet. If inventories fall, it subtracts from GDP.

- G (Government Spending): All government consumption and investment expenditure on final goods and services. Salaries for teachers and soldiers, buying military equipment, building roads. Crucial point: Transfer payments are NOT included. Social Security, unemployment benefits, welfare checks—these are just moving money around, not payment for a current service. They'll show up later in the income approach.

- NX (Net Exports = X - M): Exports (X) minus Imports (M). Goods and services produced here but sold abroad (exports) add to our GDP. Goods and services produced abroad but bought here (imports) subtract from our GDP because they were counted in the C, I, or G of other countries. A trade deficit (M > X) drags down the GDP number under this method.

So when you ask "how do you compute gdp" via spending, you're essentially doing a giant national receipt tally. The BEA gets this data from surveys of retailers, manufacturers, and from government budget records. It's comprehensive, but it has blind spots—like the underground economy or home production.

2. The Income Approach: Following the Money Earned

Now, flip the perspective. Every dollar spent by a buyer (in the expenditure approach) is a dollar of income for a seller. The money has to go somewhere. So, how do you compute GDP using the income approach? You add up all the income generated by producing those goods and services.

This gets into the nitty-gritty of national accounting. The idea is that the total value of output (GDP) gets distributed as income to the various factors of production: labor gets wages, capital gets profits and interest, land gets rent, and the government takes taxes (and gives subsidies).

The core formula here is:

Let's translate that from accountant-ese.

- Compensation of Employees: This is more than just wages. It's the total package: wages and salaries plus benefits like employer-paid health insurance, pension contributions, and social security taxes. It's all the income that goes to workers.

- Gross Operating Surplus: This is basically the pre-tax profit (or operating surplus) of corporations and government enterprises, plus depreciation (the wear and tear on capital). It's the income that accrues to capital and business owners.

- Gross Mixed Income: This is the catch-all for unincorporated businesses (like your local family-owned restaurant, a freelance graphic designer, a farmer). Their income is a "mix" of labor income and capital profit, so it's reported separately.

- Taxes on Production and Imports minus Subsidies: Sales taxes, property taxes, business license fees, import tariffs—these are income to the government from the production process. Subsidies (government payments to producers, like some farm subsidies) are subtracted because they are negative income for the government in this context.

Personally, I find this approach messier but more revealing. It shows you who is earning the nation's income—how much is going to labor vs. capital, for instance. Data comes from tax records, corporate financial statements, and labor force surveys. The IMF's Balance of Payments manual outlines these standards globally, though implementation varies.

Think of it this way: The Expenditure Approach asks, "Who bought the pie?" The Income Approach asks, "Who got the slices?"

3. The Production (Value-Added) Approach: Following the Creation Process

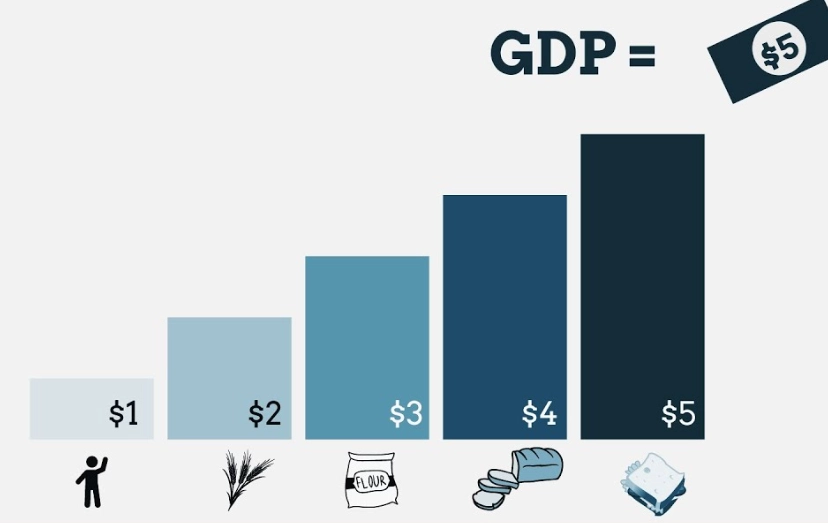

This is the method that best answers the core question of "what was produced here?" and avoids the dreaded double-counting. How do you compute GDP using the production approach? You sum up the value added at each stage of production for every industry in the economy.

Value added is simply the value of a firm's output minus the value of the intermediate goods it used up. It's the "new" value the firm created during that stage.

Let's use a classic textbook example: a loaf of bread.

- Farmer: Grows wheat, sells it to the miller for $0.50. The farmer's value added is $0.50 (no intermediate costs).

- Miller: Buys wheat ($0.50), mills it into flour, sells flour to baker for $1.20. The miller's value added is $1.20 - $0.50 = $0.70.

- Baker: Buys flour ($1.20), bakes a loaf, sells it to you at the store for $3.00. The baker's value added is $3.00 - $1.20 = $1.80.

- Retailer: (If separate) buys the loaf ($3.00), stocks it, sells it to you for $3.50. Retailer's value added is $3.50 - $3.00 = $0.50.

If you just added all the sales ($0.50 + $1.20 + $3.00 + $3.50), you'd get $8.20, massively overstating the value of the final loaf. But if you add the value added at each step ($0.50 + $0.70 + $1.80 + $0.50), you get $3.50—the final price of the loaf, which is the correct contribution to GDP.

National statistics offices use complex input-output tables to do this for the entire economy, sector by sector (manufacturing, services, agriculture, etc.). It's data-intensive but theoretically very clean. You can see detailed sectoral breakdowns in publications from the OECD, which harmonizes these across countries.

Putting It All Together: A Side-by-Side Comparison

To really lock in how these three methods relate, let's look at a simplified, consolidated view. The table below shows how the same economic activity is captured differently by each approach to answer "how do you compute gdp".

| Economic Activity | Expenditure Approach (Spending) | Income Approach (Earnings) | Production Approach (Value Added) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A factory produces and sells a machine to a business for $1 million. | Counted as $1M in Business Investment (I). | Shows up as Compensation to factory workers, Profit for factory owners, and Depreciation on factory tools. | Sum of value added by the factory and all its suppliers (steel, electronics, etc.). |

| You pay $200 for a dentist's service. | Counted as $200 in Consumption (C) of services. | Shows up as Compensation to the dentist and their staff (wages, benefits). | The dentist's value added is the $200 fee minus cost of supplies (a small amount). |

| The government builds a new road, paying a construction company $5 million. | Counted as $5M in Government Spending (G). | Shows up as Compensation to construction workers, Profit for the construction company, and Taxes paid. | Sum of value added by the construction company and its suppliers (cement, engineering services). |

| A US software company sells a license to a German firm for €500,000 (converted to $). | Counted as an Export (X), increasing Net Exports (NX). | Shows up as Compensation to US programmers and Profit for the US software company. | The value added by the US software company (mostly salaries and profit). |

See the symmetry? In a perfect world of complete and instant data, the three totals would be identical. In reality, they don't quite match due to measurement errors, timing differences, and data gaps. Statisticians then have to balance the accounts, creating a "statistical discrepancy" line to force them to align in the official reports. It's a humble reminder that even this flagship number is an estimate.

Beyond the Basics: What GDP *Doesn't* Tell You (And Why It Matters)

So you've learned how to compute GDP. But here's the critical next step: understanding what this computation leaves out. GDP is a powerful tool, but it's a terrible scorecard for societal well-being. It measures market activity, period. A lot of valuable things happen outside the market.

Let's run through a quick list of what gets missed:

- The Underground Economy: Cash-only transactions, illegal activities, under-the-table work. This can be huge in some countries. None of it shows up in official surveys or tax data, so it's missing from GDP.

- Non-Market Production: This is the big one for me. If you cook dinner at home, it adds zero to GDP. If you go to a restaurant for the same meal, it adds the bill to GDP. If you care for your aging parents at home, GDP sees nothing. Hire a home health aide, and GDP goes up. This creates a bizarre incentive in the measurement.

- Leisure Time: If everyone works 80-hour weeks, GDP might soar. But are we better off? GDP has no way to say.

- Environmental Costs and Depletion: An oil spill generates a ton of GDP from the cleanup effort. The destruction of the natural asset? Not subtracted. We count the activity of cutting down a forest as income, but not the loss of the forest stock.

- Income Distribution: GDP can rise while most people's incomes stagnate if the gains all go to the top. The "average" looks good, but the lived experience for many does not.

This isn't to say GDP is useless. Far from it. For tracking short-term economic cycles, business activity, and tax base, it's essential. Central banks like the Federal Reserve rely on GDP growth and related data to set policy. But we must be aware of its blind spots. Organizations like the OECD with its Better Life Index are trying to develop broader measures.

Final Thoughts: It's a Tool, Not a Gospel

Learning how do you compute gdp demystifies a lot of economic news. You start to see the gears turning behind the headlines. Was the growth driven by consumer spending or government stimulus? Is profit growth outstripping wage growth? The methods reveal different facets of the same complex machine.

My advice? Don't worship the number. Understand its construction, respect its utility for measuring market-scale economic activity, but always remember its profound limitations. The next time someone says "GDP is up, so everything is great," you'll know the right questions to ask: Which method showed the growth? What's driving it? And what might be happening that this number is completely ignoring?

That deeper understanding is way more valuable than just memorizing a formula. It turns you from a passive consumer of economic news into someone who can actually think critically about what it all means.