In This Article

- What Makes a Monopoly, Anyway? It's More Than Just Being Big

- How Do Monopolies Even Happen? The Path to Dominance

- The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly: The Real Impact of Monopolies

- The Regulators' Playbook: How Governments Try to Tame Monopolies

- Lessons from the Past: A Quick Tour of Historic Monopolies

- The Modern Dilemma: Are Today's Tech Giants Monopolies?

- What's Next? The Future of Monopoly Power

- Your Questions on Monopolies, Answered

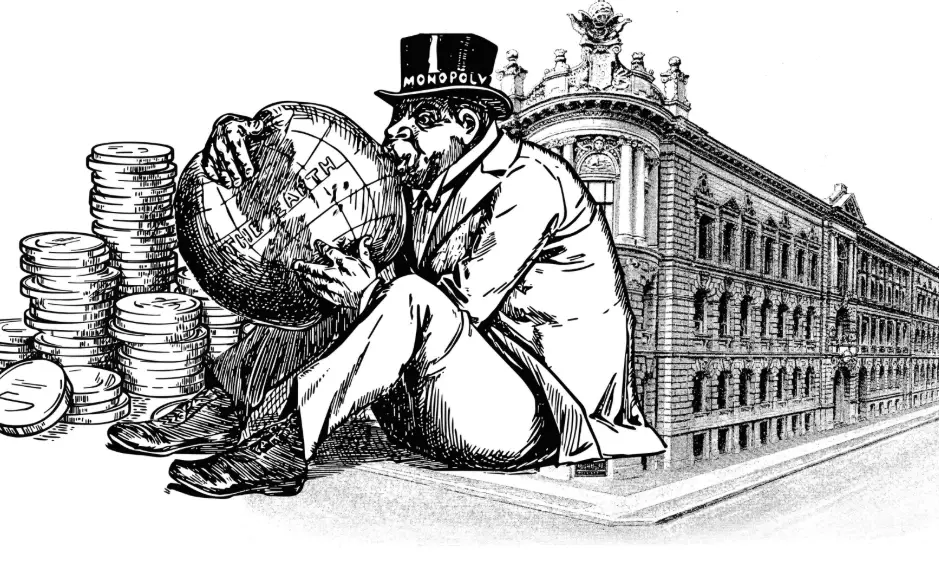

Let's talk about monopolies. It's one of those words you hear thrown around in news segments about big tech or in dusty economics classrooms, but it feels distant, abstract. Until you realize it's the reason your internet bill only has one realistic provider, or why a certain software feels impossible to avoid. A monopoly isn't just a market statistic; it's a power structure. It's a single company holding the keys to an entire market, with no real rivals to keep it in check. Sounds simple, right? The reality is a messy, fascinating, and often frustrating web of economics, law, and pure human ambition.

I remember trying to explain why breaking up a big company might be good to a friend who just wanted cheap, reliable service. It's not an easy sell. The debate around monopolies is filled with "on one hand, but on the other" arguments. Today, we're going to untangle that web. We'll strip away the jargon and look at what monopolies really are, how they sneak into existence, the tangible impact they have on your life, and why governments can't seem to make up their minds about how to handle them.

What Makes a Monopoly, Anyway? It's More Than Just Being Big

First things first, let's kill a common myth. Being a large, successful company doesn't automatically make you a monopoly. You can be huge and still have fierce competition. Think about Coca-Cola and Pepsi. The key is market power—the ability to act independently of competitive pressures. A true monopoly exists when one firm is the sole supplier of a unique product or service in a given market, with barriers so high that no one else can get in to challenge them.

Economists point to a few telltale signs:

- The Lone Seller: This is the obvious one. One company controls 100% (or so close to it that it doesn't matter) of the market supply.

- No Close Substitutes: The product or service is unique. You can't just switch to something almost like it. If you want what they're selling, you have to go to them.

- High Barriers to Entry: This is the fortress wall. These can be massive startup costs (like building a nationwide power grid), control over a key resource (like a patent on a life-saving drug), or government regulations that legally block competitors.

- Price Maker, Not Price Taker: In a competitive market, prices are set by supply and demand. A monopoly sets its own price. It can charge more because you have nowhere else to go.

A Quick Reality Check: Pure, textbook monopolies are rarer than you think. More common are near-monopolies or oligopolies (where a few giant firms dominate). The effects, however, can feel very similar to the average person.

Here’s a quick table to see how a monopoly stacks up against other market structures. It’s not always black and white, but this gives you the idea.

| Market Structure | Number of Sellers | Barriers to Entry | Control Over Price | Real-World Vibe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monopoly | One | Extremely High | Substantial | Your local water utility; a patented pharmaceutical. |

| Oligopoly | A Few | High | Some (often through tacit collusion) | Major cell phone carriers; commercial aircraft manufacturers (Boeing, Airbus). |

| Monopolistic Competition | Many | Low | Some (via product differentiation) | Restaurants, clothing brands, coffee shops. |

| Perfect Competition | Very Many | None | None | Theoretical ideal; approximated by some agricultural markets. |

How Do Monopolies Even Happen? The Path to Dominance

They don't just pop up overnight (well, mostly). There are a few main roads a company can take to reach that dominant position.

The "Natural" Monopoly: Sometimes, One Is Just More Efficient

This is the most defensible type, economically speaking. A natural monopoly arises when the most efficient way to serve a market is to have a single provider, usually because of enormous fixed costs and infrastructure. Think utilities: water, electricity, natural gas. Digging up streets to lay duplicate sets of pipes or wires for multiple competing companies is wildly inefficient and costly for society. In these cases, the monopoly is often tolerated or even created by the government, but it's heavily regulated to prevent abuse. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has detailed guidelines on how these are assessed. The trade-off is clear: you accept a lack of choice in exchange for (hopefully) stable, universally available service at a controlled price. Whether that regulation works well is a constant debate.

The Government-Created Monopoly: Patents and Licenses

Here, the government intentionally grants exclusive rights. The classic example is patents. If a pharmaceutical company spends billions developing a new drug, the government gives them a temporary monopoly (usually 20 years) to sell it without competition. The idea is to incentivize massive, risky investments in innovation. It's a bargain: society gets new medicines, and the company gets a period of high profits to recoup its costs. The problem, of course, is when drug prices skyrocket during that period, putting life-saving treatments out of reach. It's a system with built-in tension.

The "We Won Fair and Square" Monopoly (Or Did We?)

This is where it gets controversial. A company can theoretically become a monopoly through sheer superiority—a vastly better product, brilliant management, or revolutionary technology that everyone prefers. For a time, Google's search engine was so much better that it naturally dominated. The grey area, and where antitrust regulators get involved, is in the methods used to maintain that dominance. This is where we slide into...

The Anti-Competitive Monopoly: Playing Dirty

This is the classic villain story. A firm uses unfair tactics to crush competitors or block them from entering the market. Historical examples are blatant: predatory pricing (selling at a loss to drive rivals out of business), exclusive dealing contracts that lock suppliers or customers away from competitors, or outright buying up any potential threat. Modern allegations are more subtle: using control over a dominant platform (like an app store or operating system) to disadvantage rivals, or acquiring nascent competitors before they become a threat—a practice sometimes called "killer acquisitions." The U.S. Department of Justice's Antitrust Division spends most of its time investigating these kinds of behaviors. The line between aggressive competition and anti-competitive conduct is famously blurry.

I have a real problem with the argument that "the market will sort it out." When a monopoly is entrenched, the market is broken. There is no sorting mechanism left. New ideas can't get funding if they're seen as challenging an unbeatable giant. That's not competition; that's stagnation.

The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly: The Real Impact of Monopolies

So, what happens when a monopoly is in charge? The effects ripple out far beyond a company's balance sheet.

The Economic Downside (The Usual Suspects)

This is Economics 101, and it's mostly negative.

- Higher Prices: This is the big one. With no competition, a monopoly can charge more than it could in a competitive market. Consumers pay the bill directly.

- Lower Output: Strangely, monopolies often produce less than a competitive market would. Why flood the market and drive prices down when you can restrict supply and keep prices high? This leads to a net loss for society, what economists call "deadweight loss."

- Reduced Innovation: This is a huge, long-term cost. Why spend a fortune on R&D to improve your product when customers are locked in with no alternatives? The incentive to innovate plummets. Some argue monopolies can afford to innovate, but history is littered with dominant firms that grew complacent (think of old telecom monopolies before deregulation).

- Allocative Inefficiency: Resources don't flow to their best use. The monopoly's power distorts the market's natural signals.

The Less-Talked-About Social and Consumer Impact

This is where it gets personal.

- Stifled Choice and Variety: You get what the monopoly offers, in the way they offer it. Want a different feature set? A different business model? Tough luck. The market for ideas shrinks.

- Poorer Service and Quality: Again, with no fear of losing customers, where's the drive to provide excellent customer service or continuously improve quality? Complaints can fall on deaf ears.

- Political and Social Power: This might be the most dangerous effect. Massive economic power can translate into disproportionate political influence through lobbying, shaping regulations in their favor (a process called "regulatory capture"). They can also influence public discourse, media, and even cultural norms. A single company having that much sway should give anyone pause.

"Wait," you might say. "My Google services are free, and they innovate constantly!" That's the modern puzzle. In digital markets, the currency isn't always money—it's your attention and data. The price might be zero, but the cost in privacy and the sheer scale of influence is a new frontier for thinking about monopoly power. The The Economist has wrestled with this very idea, noting the challenge of applying old frameworks to new beasts.

Is There Ever an Upside?

Even critics admit there can be potential benefits, but they're highly conditional.

- Economies of Scale: A single large firm might produce at a much lower average cost, which could be passed on as lower prices (though history suggests this is the exception, not the rule).

- Stability and Standardization: In some network industries (like a railroad), a single standard can be more efficient. And a regulated utility monopoly can provide stable, universal service.

- Funding for Massive R&D: The promise of monopoly profits from a patent can fuel expensive, long-term research that scattered competitors couldn't afford. The entire modern biotech industry is built on this model.

The key is that these benefits are not automatic. They usually require the heavy hand of regulation or the ticking clock of a patent expiration to ensure the public eventually gains.

The Regulators' Playbook: How Governments Try to Tame Monopolies

Most countries have antitrust or competition laws designed to police monopoly power. In the U.S., the main tools are the Sherman Act (1890) and the Clayton Act (1914). The approach generally falls into three categories:

- Preventing Anti-Competitive Behavior: This is the most common action. Regulators sue to stop specific practices like predatory pricing, exclusive contracts, or collusion. The goal is to police how the monopoly behaves, without necessarily breaking it up.

- Blocking Mergers: The government can block mergers and acquisitions that would "substantially lessen competition" or "tend to create a monopoly." This is a preventative measure.

- Breaking Up the Monopoly (Structural Separation): This is the nuclear option. The government forces the company to divest parts of its business to create new, independent competitors. It's rare, complex, and politically charged.

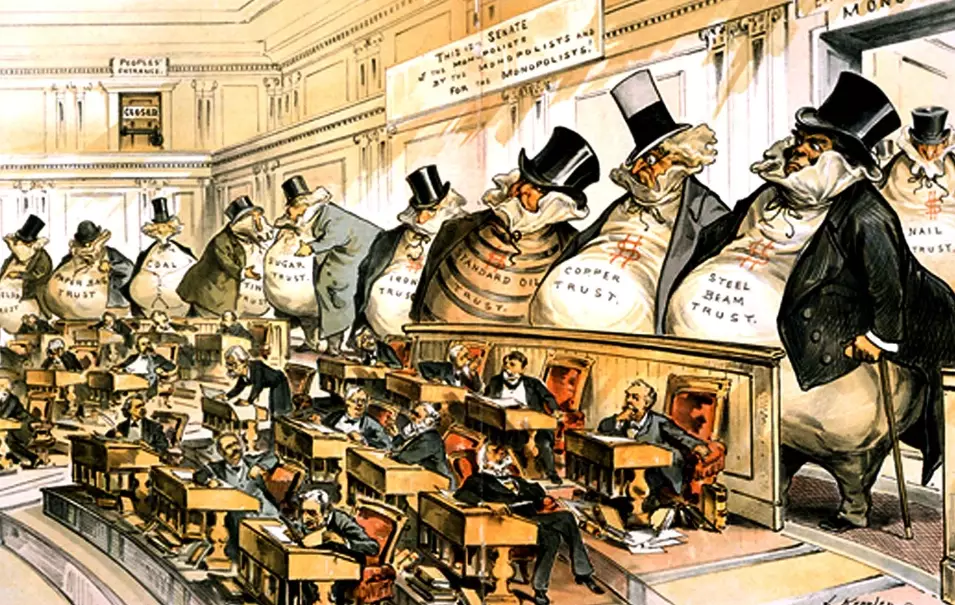

The philosophy behind enforcement swings like a pendulum. There was the aggressive trust-busting era of the early 1900s, the more laissez-faire period in the late 20th century focused on "consumer welfare" (primarily just low prices), and now a renewed, more interventionist stance questioning whether the old frameworks fit the digital age. Following the World Bank's work on competition policy shows how this is a global debate, not just an American one.

Lessons from the Past: A Quick Tour of Historic Monopolies

History is the best teacher. Let's look at two iconic cases.

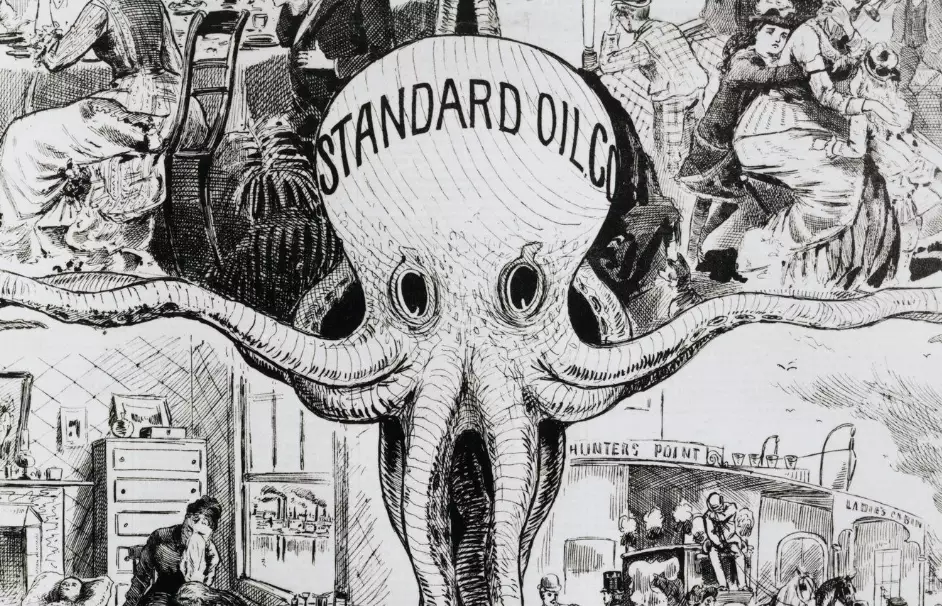

Standard Oil: The Archetype

John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil is the textbook case. By the 1880s, it controlled about 90% of U.S. oil refining. It achieved this through ruthless efficiency, secret rebates from railroads, and buying up competitors. The public and political outcry led to the Sherman Act and, eventually, the company's break-up in 1911 into 34 separate companies (including the ancestors of Exxon, Mobil, Chevron). The break-up is often cited as a success, leading to more competition and innovation in the industry. But some economists still debate whether Standard Oil's dominance was mainly due to unfair practices or simply being the best, most efficient operator.

AT&T: The Regulated Monopoly That Got Split

For most of the 20th century, AT&T ("Ma Bell") was a government-sanctioned, regulated monopoly over telephone service in the U.S. It provided universal service and funded Bell Labs, an innovation powerhouse (transistor, laser, Unix OS). But by the 1970s, it was seen as stifling new technologies like modems and early data networks. An antitrust suit led to its break-up in 1984 into a long-distance company (AT&T) and seven regional "Baby Bells." This directly unleashed the competitive chaos that led to the modern telecom and internet landscape. It's a prime example of a regulated monopoly that eventually outlived its usefulness in a changing technological world.

The Modern Dilemma: Are Today's Tech Giants Monopolies?

This is the multi-trillion-dollar question. Companies like Google (in search and online advertising), Meta (in social networking), and Amazon (in online retail and cloud services) have dominant positions in their core markets.

The arguments against calling them monopolies:

- Many of their core services are free to consumers.

- They face competition (DuckDuckGo for search, TikTok for social, Walmart and Shopify for retail).

- They innovate relentlessly and invest heavily in R&D.

- Their markets are dynamic and new competitors can emerge quickly (see the rise of TikTok).

The arguments for increased antitrust scrutiny:

- They control key "bottleneck" platforms (app stores, search rankings, social graphs) and can use that control to favor their own services or disadvantage rivals.

- They engage in serial acquisitions of potential competitors (Instagram, WhatsApp by Facebook; countless startups by Google and Amazon).

- Their power extends to data—they have monopolies on certain types of user data, which feeds their dominance in advertising and AI.

- The "price" is your attention and data, and the cost is reduced privacy and choice in the digital ecosystem.

My own take? Applying the 19th-century Standard Oil playbook directly feels clunky. But to say these firms don't possess extraordinary, monopoly-like power in key aspects of our digital lives is naive. The real debate is about what to do about it. More regulation? Break-ups? Forcing interoperability between platforms? There are no easy answers, and any action will have massive unintended consequences.

What's Next? The Future of Monopoly Power

The game is changing. We're moving into an era of potential digital and data monopolies, and soon, perhaps, AI monopolies. If a single company or a small group controls the most advanced AI models or the vast datasets needed to train them, we could see a concentration of power that makes the tech giants look quaint. Network effects are even stronger in the digital world, making winner-take-all outcomes more likely.

Globalization adds another layer. A company can be a monopoly in one country but face competition abroad. How do national regulators deal with global behemoths? It requires unprecedented international cooperation, which is in short supply.

The core challenge remains: how do we foster the efficiency and innovation that can come from scale, while preventing the stagnation, exploitation, and democratic erosion that unchecked power brings? It's a balance we've never quite gotten right, and the stakes keep getting higher.

Your Questions on Monopolies, Answered

Look, the topic of monopolies isn't just for economists and lawyers. It's about who controls the options in your life, the prices you pay, the health of the businesses in your community, and the flow of new ideas. It's about power. And understanding how that power is gained, used, and potentially checked is one of the most practical forms of economic literacy there is. The next time you hear about an antitrust lawsuit or a merger review, you'll know there's a lot more at stake than just stock prices.