In This Guide

Let's be honest. When someone says "average," what pops into your head? For most of us, it's the arithmetic mean. You add up a bunch of numbers and divide by how many there are. It's simple, it's taught in grade school, and it's everywhere. But here's the uncomfortable truth I learned the hard way: using it in the wrong situation can lead you to completely wrong conclusions. I remember once trying to calculate my average investment return over a few volatile years using the simple average, and I ended up thinking I'd done way better than I actually had. That was a wake-up call.

That's where the geometric mean comes in. It's not some obscure, theoretical concept only for mathematicians. It's a practical, powerful tool for getting the true story behind your data, especially when you're dealing with things that multiply together or change over time—like growth rates, investment returns, or ratios.

Core Idea in Plain English: The geometric mean is the central tendency you get by multiplying numbers together and then taking a root, instead of adding them. It's the natural average for multiplicative processes. If your numbers represent factors (like "grew by 1.5 times"), the geometric mean is your friend.

What Exactly Is the Geometric Mean? Breaking Down the Intuition

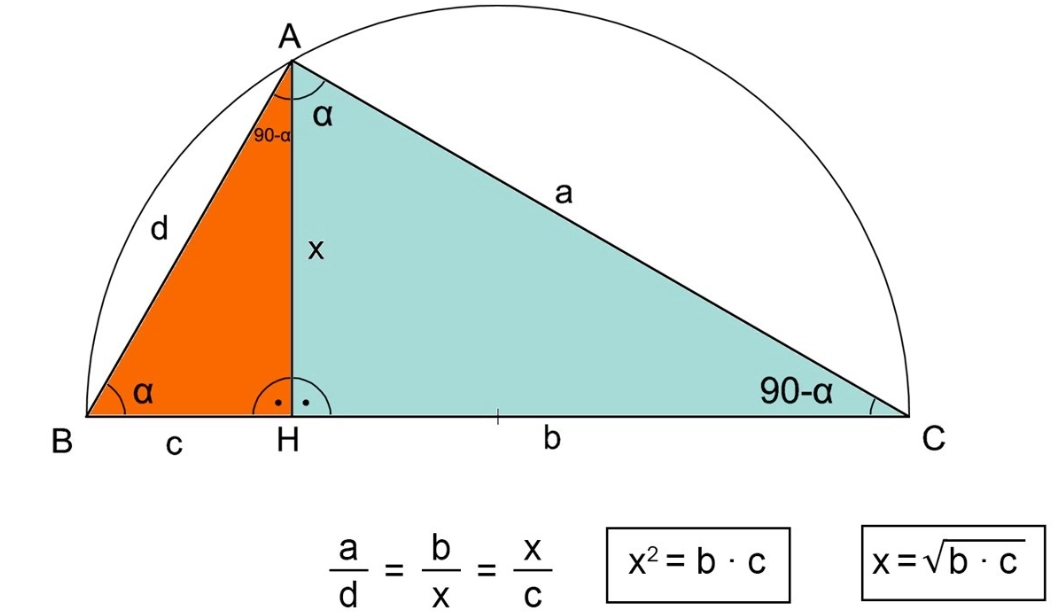

Forget the formula for a second. Think about what an average should do. The arithmetic mean finds the number that, if you added it to itself N times, you'd get the same total as the sum of your original numbers. The geometric mean asks a different question: what's the number that, if you multiplied it by itself N times, would give you the same product as multiplying all your original numbers together?

That shift from addition to multiplication is everything. It makes the geometric mean inherently sensitive to proportional changes. A 50% increase (a multiplier of 1.5) and a 50% decrease (a multiplier of 0.5) don't cancel out to "no change" in a multiplicative world. Multiply them: 1.5 * 0.5 = 0.75. You've lost 25% overall. The arithmetic mean of 1.5 and 0.5 is 1.0 (or 0% change), which is misleading. The geometric mean gives you √(1.5 * 0.5) = √0.75 ≈ 0.866, telling you the average multiplier per period was 0.866, meaning you lost about 13.4% per period on average. That's the reality.

So, when should this intuition guide you? I'd say whenever you see the word "rate," "return," "growth," or "index," you should at least pause and consider the geometric mean.

The Nuts and Bolts: How to Calculate the Geometric Mean

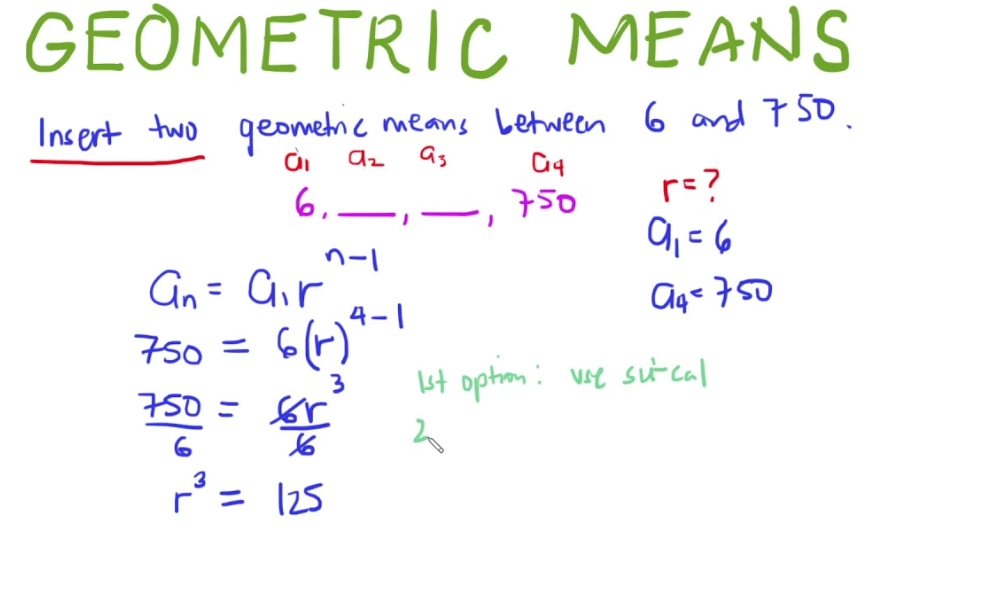

Alright, let's get into the mechanics. The formula is elegantly simple:

Geometric Mean = ⁿ√(x₁ * x₂ * x₃ * ... * xₙ)

Where 'n' is the number of values, and that 'n' before the root symbol means you're taking the n-th root (square root for two numbers, cube root for three, etc.).

Hands-On Example: Let's calculate the average annual growth rate of a company's revenue over three years:

Year 1: +20% (value = 1.20)

Year 2: -10% (value = 0.90)

Year 3: +15% (value = 1.15)

Step 1: Multiply the factors: 1.20 * 0.90 * 1.15 = 1.242

Step 2: Take the cube root (because there are 3 years): ³√1.242 ≈ 1.075

Step 3: Interpret: The geometric mean is approximately 1.075, meaning the average annual growth rate was about 7.5%.

Check the arithmetic mean? (20% + (-10%) + 15%) / 3 = 8.33%. That overstates your true, compounded performance.

You can also use logarithms. It sounds fancy, but it's just another way to get there, and it's often easier for spreadsheets or calculators: GM = exp( (ln(x₁) + ln(x₂) + ... + ln(xₙ)) / n ). This converts multiplication into addition, finds the average of the logs, and then converts back.

A Major Gotcha: You cannot calculate the geometric mean if any of your numbers are zero or negative (unless you're using complex numbers, which is a whole other world for most practical applications). Why? Because the product becomes zero or negative, and taking the root of a negative number with an even root isn't defined in real numbers. This is a real limitation. If your dataset has zeros or negatives, you often have to use a different measure or transform the data carefully.

Geometric Mean vs. Arithmetic Mean: The Showdown

This is the heart of the confusion for many people. When do you use which? They're different tools for different jobs.

The arithmetic mean is perfect for independent, additive data. Think of things like heights of people in a room, daily temperatures, or test scores. These values don't interact with each other; one person's height doesn't multiply another's.

The geometric mean is the champion for interdependent, multiplicative data. Think of sequential growth. Your investment return in year 2 applies to the portfolio that resulted from year 1's return. They compound. This interdependence is key.

Here’s a table to make the distinction crystal clear:

| Scenario / Data Type | Use Arithmetic Mean | Use Geometric Mean | Why? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Test Scores | ✅ Yes | ❌ No | Scores are independent. A 90 and a 70 average to 80. |

| Average Annual Investment Returns | ❌ Misleading! | ✅ Essential | Returns compound multiplicatively. The geometric mean gives the true compounded annual growth rate (CAGR). |

| Average Speed for a Round Trip (different distances) | ❌ Wrong | ✅ Correct (in harmonic mean form*) | Speed is a rate per unit time. The average is based on total distance/total time, which leads to the harmonic mean, a cousin of the geometric mean. |

| Average of Ratios or Index Numbers (e.g., P/E ratios across stocks) | ❌ Can be skewed | ✅ Often better | Ratios are inherently multiplicative. The geometric mean is less skewed by extreme outliers. |

| Population Growth Over Time | ❌ Inaccurate | ✅ Accurate | Growth is multiplicative. The geometric mean provides the consistent rate needed to get from start to finish. |

*The harmonic mean is another Pythagorean mean, used for rates like speed. It's part of the same family of "non-arithmetic" averages.

A rule of thumb that's served me well: If the data can be sensibly added, use the arithmetic mean. If the process is better described by multiplying, use the geometric mean. Ask yourself: "Do these numbers represent steps in a chain of multiplication?" If yes, reach for the geometric mean.

Where You'll Actually Use the Geometric Mean: Real-World Applications

This isn't just textbook stuff. The geometric mean pops up in fields where accuracy in growth and proportions matters most.

Finance and Investing: The Home of CAGR

This is the classic, non-negotiable use case. The Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) is literally the geometric mean of a series of annual growth factors. If an investment goes from $100 to $150 over 3 years with varying returns, the CAGR tells you the single, steady rate that would have gotten you to the same end point. Any financial analyst using the arithmetic mean for multi-period returns is making a fundamental error. Resources like Investopedia's guide to CAGR explain this from an investor's perspective.

Science and Environmental Studies

In biology, it's used to average exponential growth rates of bacteria. In environmental science, it's often the recommended way to average pollution concentration data over time. Why? Because environmental data is often log-normally distributed (skewed), and the geometric mean provides a better central value than the arithmetic mean, which gets pulled up by high outliers. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has guidelines on this for certain water quality metrics.

Social Sciences and Economics

When comparing indices across countries with vastly different sizes—like per capita income—the geometric mean can help create a more balanced composite index. It prevents large economies from dominating the average simply due to their scale. You can see this principle in some international development indices.

Computer Science and Image Processing

In signal processing, the geometric mean can be used as a filter that preserves edges better than an arithmetic mean filter. It's also used in some machine learning algorithms when dealing with normalized data or similarity scores that are multiplicative in nature.

Tackling the Tricky Bits: FAQs and Common Hurdles

Let's address the questions that usually trip people up. I know these were the ones I had to look up.

When exactly should I NOT use the geometric mean?

Don't use it for data that is additive by nature. Don't use it if your dataset contains any zeros or negative numbers (unless you have a specific, advanced reason and know how to handle it). Also, if your numbers are on an interval scale without a true zero (like temperature in Celsius), the geometric mean isn't meaningful because the ratios aren't interpretable. 20°C is not "twice as hot" as 10°C.

Is the geometric mean always smaller than the arithmetic mean?

For any set of positive numbers that are not all identical, the geometric mean is always less than or equal to the arithmetic mean. This is a mathematical fact. The more spread out or variable your numbers are, the bigger the gap between the two means. This property is why using the arithmetic mean for growth rates is so optimistic—it ignores the volatility drag.

How do I handle zeros in my data if I need a geometric mean?

This is a tough one. A single zero makes the product zero, so the geometric mean is zero, which often isn't useful. Common workarounds include: 1) Adding a very small constant to all values (like 0.001), but this biases the result. 2) Using a different average altogether, like the median. 3) If the zeros represent a separate process (like no growth), you might need to analyze the data in two parts. There's no perfect answer; it depends on what the zero means in your context.

Can I use a geometric mean calculator online?

Absolutely, and you should to check your work! But understand what it's doing. A good geometric mean calculator will simply multiply your entries and take the n-th root. Just be sure you're entering the correct numbers (e.g., 1.10 for 10% growth, not 10).

What's the deal with the geometric mean and the "normalization" of data?

This is a more advanced but crucial point. When you have datasets on completely different scales (e.g., comparing a country's GDP, life expectancy, and education index), you often normalize them first (scale them to a common range). If you then take an arithmetic mean of these normalized scores, a high score in one area can compensate for a low score in another. The geometric mean of normalized scores doesn't allow for perfect compensation like that. A low score in one dimension will drag down the overall geometric mean more significantly. This property is why it's used in indices like the Human Development Index (HDI)—it encourages balanced development across dimensions.

My Personal Take: Learning about the geometric mean felt like getting a secret decoder ring for the financial world. Suddenly, fund performance reports and economic growth statistics made more sense. I was no longer just accepting the "average return" figure at face value. I started asking, "Is that the arithmetic or geometric mean?" It's a small piece of knowledge that significantly boosts your data literacy.

Putting It All Together: A Step-by-Step Decision Guide

Feeling overwhelmed? Let's simplify the decision process into a flow you can follow.

- Look at your numbers. Are any of them zero or negative? If yes, the standard geometric mean is likely off the table. Consider the median or analyze the data in segments.

- Ask about the process. Are the numbers the result of a multiplicative process? (e.g., sequential growth rates, repeated application of a multiplier). If YES → Strong candidate for the geometric mean.

- Ask about independence. Are the numbers independent items? (e.g., weights of different apples, salaries in a department). If YES → The arithmetic mean is probably fine.

- Ask about ratios or indices. Are you averaging ratios, percentages, or index numbers? If YES → The geometric mean is often more robust, especially if the values span different orders of magnitude.

- Calculate both. When in doubt, calculate both the arithmetic and geometric means. If they are very close, the data is fairly consistent, and the arithmetic mean is simpler to explain. If they are far apart, your data is volatile or skewed, and the geometric mean is almost certainly the more truthful representation of the central tendency.

The geometric mean isn't a replacement for the arithmetic mean. It's a complementary tool. Having both in your toolkit allows you to interrogate your data more deeply and avoid the common pitfall of using a one-size-fits-all average. It forces you to think about the nature of your data, which is always a good thing.

So next time you see an "average" rate, pause. Think about the geometric mean. It might just save you from a misleading conclusion. It's more than a formula; it's a way of seeing the world through the lens of compounding and proportional change. And in a world full of growth metrics and performance indicators, that's a perspective worth having.