Quick Guide

- The Nuts and Bolts: How Does a Put Option Actually Work?

- Why Would You Ever Buy a Put Option? The Three Big Reasons.

- Okay, I'm Interested. How Do I Actually Buy or Sell a Put?

- What Makes a Put Option Expensive or Cheap? Understanding Premiums.

- Common Put Option Strategies (Beyond Just Buying One)

- Frequently Asked Questions About Put Options

- Final Thoughts: Respect the Tool

Let's talk about put options. If you've ever worried about your stocks taking a nosedive, or maybe you've had a hunch that the market is about to turn sour, you've probably stumbled across this term. It sounds complex, maybe a bit intimidating, like something only Wall Street pros should mess with. I used to think that too. But here's the thing – once you peel back the jargon, a put option is actually a pretty straightforward concept. It's a tool. And like any tool, it can be used to build something solid or, if you're not careful, to smash your thumb.

At its heart, a put option is a contract. It gives you the right, but not the obligation, to sell a specific asset (like 100 shares of a company's stock) at a predetermined price (the "strike price") within a set period of time. You pay a fee for this right, called the "premium." Why would you want that right? Two main reasons: to protect yourself or to make a bet.

Honestly, the first time I bought a put option, my palms were sweaty. I was holding shares in a tech company that had run up a lot, and earnings were coming up. I was nervous. Buying that put felt like buying peace of mind. It didn't make me money in that instance, but it let me sleep at night. That's a real, practical use that doesn't get talked about enough in the cold, hard numbers of finance.

The Nuts and Bolts: How Does a Put Option Actually Work?

Okay, so you have this contract. Let's break down the key players and terms, because without this, the whole thing is just noise.

First, there are always two sides to every options contract. You have the buyer and the seller (also called the writer). When you buy a put option, you are buying the right to sell. You're the one who might want insurance or who's betting on a drop. When you sell a put option, you are on the hook. You're selling someone else that right. In return for collecting the premium upfront, you promise to buy the shares at the strike price if the buyer decides to exercise the option. Selling puts is a whole different ballgame, often used by people who are willing to buy a stock at a lower price.

The main ingredients in any put option recipe are:

- The Underlying Asset: This is what the contract is about. Usually, it's 100 shares of a specific stock (like Apple or Tesla), but it can also be an ETF, an index like the S&P 500, or even commodities.

- The Strike Price: This is the "locked-in" sale price. If you own a put option with a $150 strike price, you have the right to sell the stock for $150 per share, no matter how low it plummets in the market.

- The Expiration Date: Options aren't forever. They have an expiry—a specific date when the contract becomes worthless. You have to make your move before this date. There are weekly, monthly, and even quarterly expirations.

- The Premium: This is the price you pay to buy the put option (or the money you receive if you're selling it). It's determined by a bunch of factors we'll get into, like how far away the strike price is, how much time is left, and how volatile the stock is.

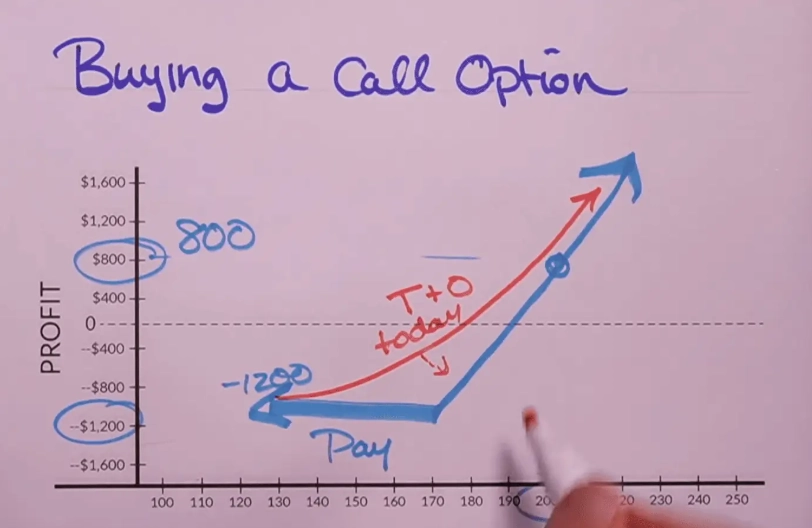

So, what happens in different scenarios? Let's say you buy a put option on XYZ stock, which is trading at $100. You buy one put contract (representing 100 shares) with a $95 strike price, expiring in one month, for a premium of $3 per share ($300 total).

| Scenario at Expiration | What Happens to Your Put Option | Your Financial Outcome (per contract) |

|---|---|---|

| XYZ stock crashes to $80 | Your put is "in the money." You can sell shares at $95 that are only worth $80. Very valuable. | You can profit. Profit = (Strike $95 - Market $80 - Premium $3) * 100 = $1,200. You'd likely just sell the option itself for a profit. |

| XYZ stock is at $96 | Your put is still "in the money" but only by $1. | You might break even or have a small loss, depending on the remaining premium value. The option still has some value. |

| XYZ stock is above $95 (e.g., $97, $100, $110) | Your put is "out of the money." No one would use their right to sell at $95 when the market price is higher. | The option expires worthless. Your maximum loss is the premium you paid: -$300. |

See? The buyer's risk is capped at the premium paid. That's a huge point. Your downside is known and limited from the moment you buy. The potential upside, if the stock goes to zero, is substantial (strike price minus premium). For the seller, it's the opposite: limited profit (the premium), but theoretically unlimited risk if the stock crashes hard.

Why Would You Ever Buy a Put Option? The Three Big Reasons.

People don't just trade these things for fun. Well, some do, but that's a path to the poorhouse. There are three primary, sensible motivations for using put options.

Hedging: Your Portfolio's Safety Net

This is the classic, prudent use. You own shares of a company you believe in long-term, but you're worried about a short-term drop—maybe because of an upcoming earnings report, a Fed announcement, or general market jitters. Buying a put option on those shares is like taking out an insurance policy.

If the stock falls, the increase in the value of your put option helps offset the loss in your stock holdings. It's not a perfect one-to-one hedge usually, but it softens the blow. The cost? The premium. You're paying for peace of mind. Is it worth it? Sometimes, absolutely. It turns a potential catastrophe into a manageable cost.

Speculation: Betting on a Decline

This is the more aggressive use. You don't own the stock, but you think it's going down. Buying a put allows you to profit from that decline with much less capital than, say, short selling the stock directly. Remember, your max loss is the premium.

Let's be real, this is hard. You need to be right about the direction, the magnitude, and the timing of the move. Get one wrong, and your put can expire worthless even if you were right about the stock going down eventually. Timing the market is a fool's errand most of the time, and speculative put buying plays right into that trap. I've lost more money than I care to admit trying to be clever with speculative puts.

Generating Income (Selling Puts)

This is for the sellers. If you're neutral to bullish on a stock—you think it will stay the same or go up—you can sell a put option and collect the premium. If the stock stays above the strike price, you keep the full premium as profit. Your hope is that the option expires worthless.

Many investors use this as a way to potentially buy a stock they like at a discount. You sell a put with a strike price below the current market price. If the stock dips to that level and you get assigned, you buy it at your target price and you got paid the premium to wait. Not a bad deal. But again, the risk is being forced to buy if the stock crashes way below your strike.

Okay, I'm Interested. How Do I Actually Buy or Sell a Put?

It's not like buying a stock, but it's not rocket science either. You need a brokerage account that supports options trading. Not all do, and they'll usually require you to apply and be approved for a certain "options level," which assesses your experience and risk tolerance.

Once approved, the process looks something like this:

- Choose Your Underlying Stock: Start with a company you know well. Don't jump into options on some volatile biotech stock you just heard about on a forum.

- Analyze and Form a View: For a protective put, you already own it and are worried. For a speculative put, you need a strong conviction it will fall within a specific timeframe.

- Open the Options Chain: In your brokerage platform, find the stock and look for the "Options" tab. You'll see a table (the "options chain") littered with strike prices and expiration dates for both calls and puts.

- Pick Your Strike and Expiration: This is the art part.

- For Hedging: You might choose a strike price slightly below the current price ("out of the money") to keep the premium cost lower. The expiration should cover your period of worry.

- For Speculation: It depends on how confident and aggressive you are. An "at the money" put (strike near current price) is more expensive but reacts more to price moves. A cheaper, deep "out of the money" put needs a huge move to pay off.

- Place the Order: You'll select "Buy to Open" for buying a put or "Sell to Open" for selling one. You can use limit orders to control the price (premium) you pay or receive. Don't use market orders on options—the spread can kill you.

- Manage or Close the Position: You don't have to hold until expiration. Most options traders close their positions by selling the option they bought ("Sell to Close") or buying back the option they sold ("Buy to Close") to lock in a profit or cut a loss.

The interface can look intimidating with all those numbers—bid, ask, last price, volume, open interest, Greeks (Delta, Gamma, Theta, Vega). For your first trade, focus on the bid/ask spread (try to buy at the ask or lower, sell at the bid or higher) and the expiration date. The Greeks are important for advanced management, but you can learn those later.

A piece of advice? Paper trade first. Use a simulator. Get a feel for how the prices move before risking real cash.

What Makes a Put Option Expensive or Cheap? Understanding Premiums.

You look at two puts on the same stock with different strikes or expirations, and the prices are wildly different. Why? The premium isn't arbitrary. It's mostly made up of two components: intrinsic value and time value, influenced by a few key factors.

Intrinsic Value is the concrete, real-money value of the option if you exercised it right now. For a put option, it's the amount the strike price is above the current stock price. If the strike is $100 and the stock is $90, the put has $10 of intrinsic value. An "in the money" put has intrinsic value. An "at the money" or "out of the money" put has zero intrinsic value.

Time Value is everything else. It's the premium you pay for the possibility that the stock could move in your favor before expiration. Time value decays as the expiration date gets closer—a process called "theta decay." This decay accelerates in the final weeks. It's the enemy of the option buyer and the friend of the seller.

The main drivers of an option's premium (its time value specifically) are:

- Time to Expiration: More time = higher premium. There's more opportunity for the stock to move.

- Implied Volatility (IV): This is a huge one. IV reflects the market's expectation of future price swings. High IV (like before earnings or during a market crisis) means higher option premiums because big moves are expected. Low IV means cheaper premiums. Buying options when IV is high is often expensive, like buying insurance when a hurricane is forecasted.

- Distance from Strike Price: A deep "in the money" put has high intrinsic value and lower time value. A deep "out of the money" put is all time value (and hope). "At the money" options usually have the highest time value.

- Interest Rates: Has a smaller effect, but generally, higher rates can slightly decrease put premiums.

So, if you're buying a protective put and want to minimize cost, you might pick one that's slightly out of the money and with an expiration not too far out, while avoiding periods of sky-high implied volatility if you can.

Common Put Option Strategies (Beyond Just Buying One)

Once you get the basics, you can combine options into strategies. Here are a few common ones involving puts.

The Protective Put (Married Put): We covered this. Buy stock, buy a put. It's a direct hedge. Simple and effective.

The Long Put: Just buying a put outright for speculation. Maximum risk: premium paid. Potential reward: substantial.

The Put Spread: This limits your cost and your potential profit. You buy one put option at a certain strike and sell another put option at a lower strike on the same stock with the same expiration. The premium you receive from selling the second put offsets the cost of the one you bought. Your max profit is capped at the difference between the strikes minus the net premium paid. It's a more defined-risk way to bet on a moderate drop.

The Collar: A popular strategy for holding a stock you like but want to protect in the short term. You own the stock, you buy a protective put (to limit downside), and you sell a covered call (a call option against your shares) to help pay for the put premium. It limits both your downside and your upside. It's a neutral strategy.

| Strategy | When You Use It | Max Risk | Max Reward | Market Outlook Required |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protective Put | Own stock, fear a drop | Stock loss - Put gain + Premium Paid | Stock upside - Premium Paid | Bullish long-term, bearish short-term |

| Long Put | Speculate on a drop | Premium Paid | High (if stock goes to zero) | Bearish |

| Bear Put Spread | Speculate on a moderate drop | Net Premium Paid | (Strike Diff - Net Premium) | Moderately Bearish |

| Collar | Protect gains on a stock | Limited (by long put) | Limited (by short call) | Neutral |

Frequently Asked Questions About Put Options

Let's tackle some of the real questions people type into Google.

Final Thoughts: Respect the Tool

Put options are powerful. They can be the smartest move in your investing playbook, providing affordable insurance and letting you manage risk in a way that simply selling a stock doesn't. The ability to define your maximum loss upfront is a beautiful thing in the messy world of finance.

But they can also be a quick way to lose money if used recklessly—especially on the selling side or for pure, short-term speculation. The time decay is a relentless force working against the buyer.

My journey with them started with that nervous hedge, and over time I've learned to use them sparingly and with clear purpose. I don't use them often, but when I do, it's because I have a specific, defined goal: "I want to protect this position through earnings" or "I am willing to pay X dollars to limit my downside on this trade to Y."

Start small. Use them to hedge a position you already understand. Get a feel for how the premium moves with the stock price and with time. Forget about getting rich quick with speculative puts. Focus on the risk-management aspect first. The financial markets are risky enough; having a tool like a put option in your toolkit to manage that risk is, in my opinion, a sign of a sophisticated investor, not a gambler. Just make sure you're the one holding the tool, and not the other way around.

Want to dive deeper into the math? Sites like Investopedia have deep dives on the "Greeks" (Delta, Theta, etc.) that govern option pricing. It's the next step once you're comfortable with the basic why and how of the put option contract.