In This Article

Let's be honest. When you first hear the term "Efficient Market Hypothesis," it sounds like some dry, academic theory cooked up by professors who've never placed a real trade in their lives. I thought the same thing. The name itself is a mouthful. But then I started investing, and the questions piled up. Why do most professional fund managers fail to beat the market? Is technical analysis just fancy guesswork? Can anyone, including me, actually find an "edge"?

That's when the efficient market hypothesis, or EMH, stopped being a theory and started feeling very, very relevant. It's not about complex math. It's a simple, powerful idea about how markets work. And depending on who you ask, it's either the most important insight in finance or a completely flawed fairy tale.

I'm not here to sell you on one side or the other. What I want to do is break it down, strip away the jargon, and look at what the evidence actually says. Because whether you're a buy-and-hold index fund investor or someone who loves digging for undervalued stocks, understanding this concept will change how you see every chart, every news headline, and every stock tip.

The Core Idea: At its heart, the efficient market hypothesis states that stock prices already reflect all available information. That's it. The current price of Apple or Tesla isn't just a random number—it's the market's best collective guess at its value, based on everything everyone knows. This means it's impossible to consistently "beat the market" because any new information is instantly baked into the price.

Where Did This Idea Even Come From?

The seeds were planted by a French mathematician, Louis Bachelier, way back in 1900. But the modern version really took off in the 1960s with economist Eugene Fama (who later won a Nobel Prize for this work). Fama looked at the data and saw something fascinating: stock price movements seemed to follow a "random walk." Tomorrow's price change was essentially unrelated to today's. If patterns were easy to spot, everyone would see them and trade on them, eliminating the profit opportunity instantly.

This was a radical shift in thinking. It challenged the entire foundation of active stock picking and market timing. The implications are massive. If the market is efficient, then spending hours analyzing charts or financial statements is mostly a waste of time. The best you can do is buy the whole market and hold it.

It sounds depressing for active traders, doesn't it? But hold on, the story isn't that simple.

The Three Flavors of Market Efficiency

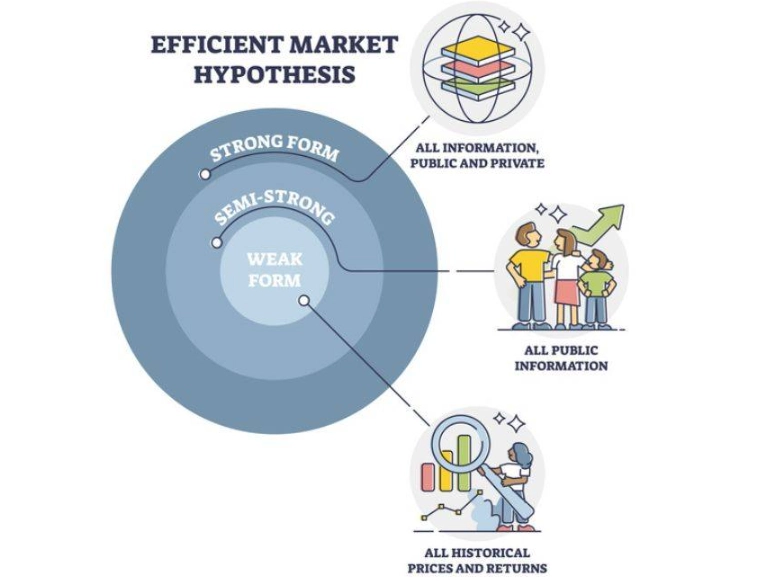

One of the biggest misunderstandings is treating EMH as a single, monolithic rule. It's not. Eugene Fama himself proposed three levels, or "forms," of the efficient market hypothesis. Think of them as weak, semi-strong, and strong. The difference lies in what type of information is already reflected in the price.

| Form of EMH | What Information is Reflected in Price? | Can You Beat the Market Using...? | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weak Form | All past market data (historical prices, trading volume). | Technical Analysis? No. Chart patterns are useless. Fundamental Analysis? Maybe. |

"Buy low, sell high" based on charts is futile. Momentum or mean-reversion strategies based purely on price history shouldn't work. |

| Semi-Strong Form | All public information (past data, financial reports, news, economic data). | Fundamental Analysis? No. Public info is already priced in. Insider Information? Yes (but it's illegal). |

You can't gain an edge by reading annual reports or news faster than anyone else. The market reacts almost instantly. |

| Strong Form | All information, both public and private (insider info). | Any Analysis or Insider Info? No. Even insiders can't profit. | This is the strongest version and is widely considered unrealistic. It suggests no one, not even company executives, can consistently profit from non-public knowledge. |

Most of the debate today revolves around the semi-strong form. The weak form is pretty well accepted—most academic studies show that technical analysis doesn't offer reliable, risk-adjusted excess returns over the long run. The strong form is mostly rejected because we have clear laws against insider trading, which proves that private information can be valuable. So, the battleground is the semi-strong efficient market hypothesis.

The Evidence For Market Efficiency

Let's look at the arguments that make the efficient market hypothesis so compelling. It's not just theory; there's a mountain of data backing it up.

First, and this is the big one for me: the consistent underperformance of active managers. Study after study shows that over 10-15 year periods, a vast majority of actively managed mutual funds fail to beat their benchmark index after fees. The SPIVA scorecards from S&P Dow Jones Indices are a brutal, twice-yearly reminder of this fact. If professional, full-time teams with vast resources can't do it consistently, what chance do I have in my spare time?

Second, the rapid reaction to news. Think about an earnings surprise or a merger announcement. The stock price gaps up or down within seconds, sometimes before you can even finish reading the headline. By the time the news is public, the adjustment is over. This is a direct observation supporting the semi-strong form. You can see this in action on any financial news website—prices move almost instantaneously with headlines.

Third, the rise and dominance of index funds. This is the real-world proof. The entire philosophy of Vanguard's founder, John Bogle, was built on the logic of market efficiency. Why pay high fees to try and beat the market when you can just own it cheaply? The trillions of dollars flowing into index funds and ETFs aren't there by accident. It's a massive vote of confidence in the core idea that consistently picking winners is extraordinarily difficult. You can read about Bogle's philosophy directly from the source on the Vanguard website.

My Personal Takeaway: After years of trying to pick stocks, I finally looked at my own portfolio returns. They were decent, but they lagged the S&P 500. The time spent researching? Enormous. The stress? High. I had a moment where I realized I was the data point proving the efficient market hypothesis right, at least for an amateur like me. Swapping to a simple, low-cost index portfolio was one of the best financial decisions I ever made. It felt like admitting defeat, but it was actually embracing reality.

The Big Challenges and Criticisms

Okay, so if markets are so efficient, how do we explain bubbles like the Dot-Com crash or the 2008 Housing crisis? Why do we see legendary investors like Warren Buffett who seem to beat the market for decades? This is where the critics have a field day, and honestly, their points are strong.

The field of behavioral finance is the arch-nemesis of the pure efficient market hypothesis. Pioneered by psychologists like Daniel Kahneman (another Nobel winner) and economists like Robert Shiller, it argues that markets are not rational. Investors are driven by emotions like greed, fear, and herd mentality. We're overconfident, we chase trends, and we hate losses more than we love gains. These predictable biases can and do create mispricings that last for years. Shiller's work on market volatility, which you can find in his seminal paper "Do Stock Prices Move Too Much to Be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Dividends?", directly challenged the notion of perfect efficiency.

Then there are the market anomalies. These are persistent patterns that seem to contradict the random walk. A few well-documented ones include:

- The Value Effect: Stocks with low price-to-book ratios (value stocks) have historically outperformed growth stocks over very long periods.

- The Small-Cap Effect: Smaller companies have historically offered higher returns than large companies.

- The January Effect: A historical tendency for stocks to rise more in January.

Proponents of EMH argue that these anomalies are either statistical flukes, a compensation for higher risk (value and small-cap stocks are riskier), or that they disappear once discovered because traders arbitrage them away. Critics say they are clear cracks in the efficient market armor.

A Common Myth: "If markets are efficient, then investing is just gambling." This is completely wrong. In an efficient market, investing is about owning productive assets and earning a return for bearing risk. Gambling is a zero-sum game with no underlying economic value. Investing in an efficient market is about participating in the growth of the economy, not outsmarting others.

What Does This Mean For You, The Investor?

This is the only section that really matters. Forget the academic debate. How should the efficient market hypothesis change what you do with your money?

If You Lean Towards Believing EMH (The Pragmatist's Path):

Your strategy is simple and powerful. Focus on asset allocation, not stock selection. Build a diversified portfolio of low-cost index funds (like total market or S&P 500 funds) and ETFs. Minimize fees and taxes. Automate your contributions. Your goal isn't to beat the market; it's to own the market and capture its long-term returns. This is the core philosophy behind the Bogleheads investment philosophy, a fantastic resource for everyday investors.

If You Lean Towards Rejecting EMH (The Active Path):

You believe markets are somewhat inefficient due to human behavior. Your edge comes from discipline, deep research, and exploiting emotional extremes. This could mean a value investing approach (buying unpopular, undervalued companies), a systematic factor-based approach (targeting value, momentum, or quality factors), or contrarian investing. The key is understanding this is incredibly hard work, requires immense patience, and still might not work. You are competing against algorithms and professionals.

Frequently Asked Questions (The Stuff You Actually Google)

The Bottom Line: A Practical Synthesis

After all this, where do I land? I don't think the market is perfectly efficient. Human psychology guarantees it can't be. But I think it's ferociously competitive and highly efficient. The difference is crucial.

For 99% of individual investors, acting as if the semi-strong efficient market hypothesis is true is the wisest, most stress-free, and most statistically likely path to long-term wealth. The effort, cost, and emotional toll of trying to be the next Buffett or to time the market are just not worth the probable outcome of underperformance.

The real power of understanding the efficient market hypothesis isn't in proving it right or wrong. It's in giving you a robust framework to ignore the noise. It helps you tune out the daily financial news panic, the hot stock tips, and the fear of missing out on the next big thing. It brings the focus back to the few things you can control: your savings rate, your diversification, your costs, and your own behavior.

So, can you beat the stock market? The efficient market hypothesis suggests the odds are heavily stacked against you. But the beautiful part is, you don't need to beat it. You just need to own it, be patient, and let compound interest do the hard work. That’s a hypothesis with a track record anyone can get behind.